Psalm 89 Poetry

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: Poetic Structure and Poetic Features.

Poetic Structure

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Macro-structure

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

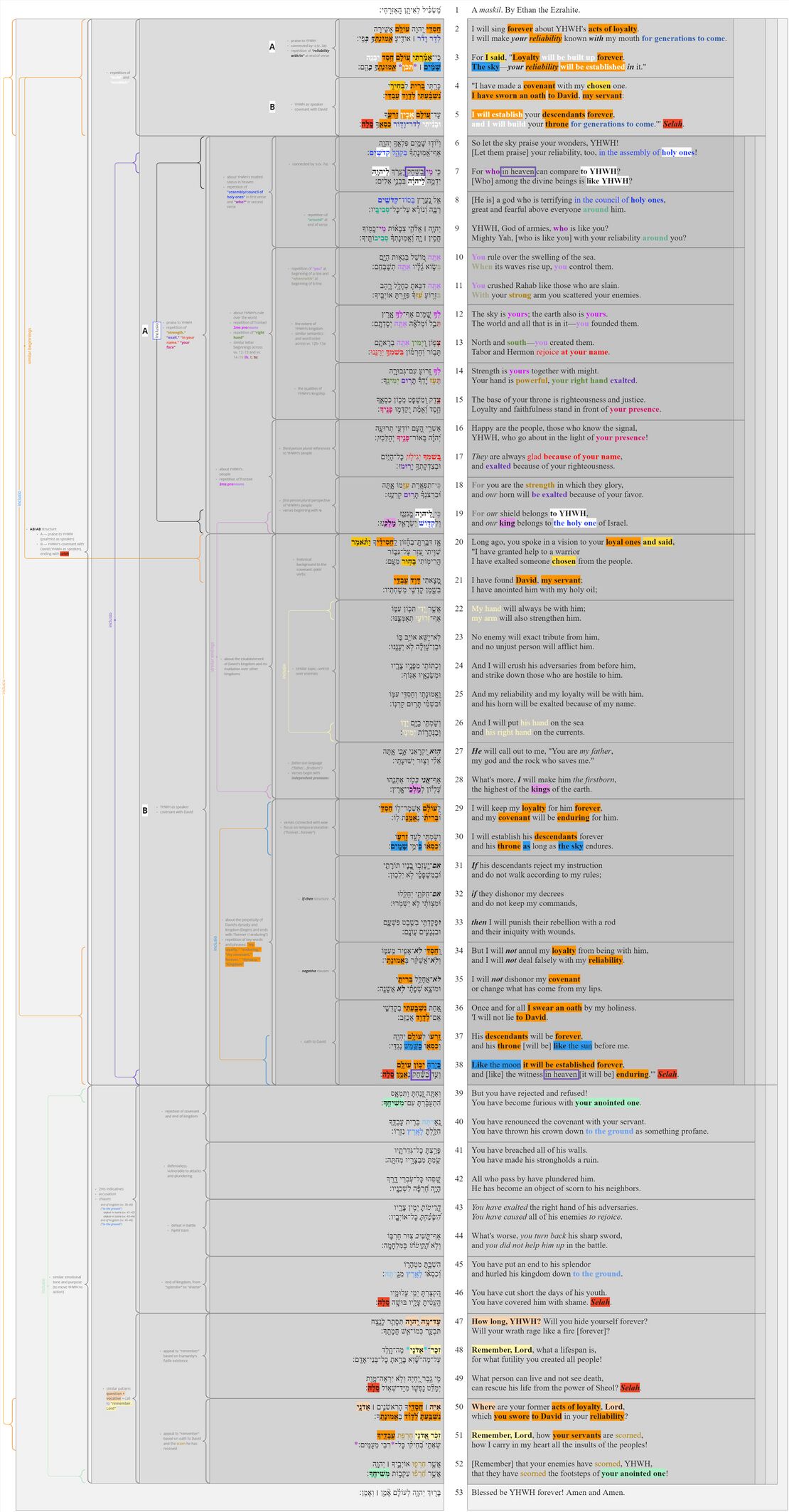

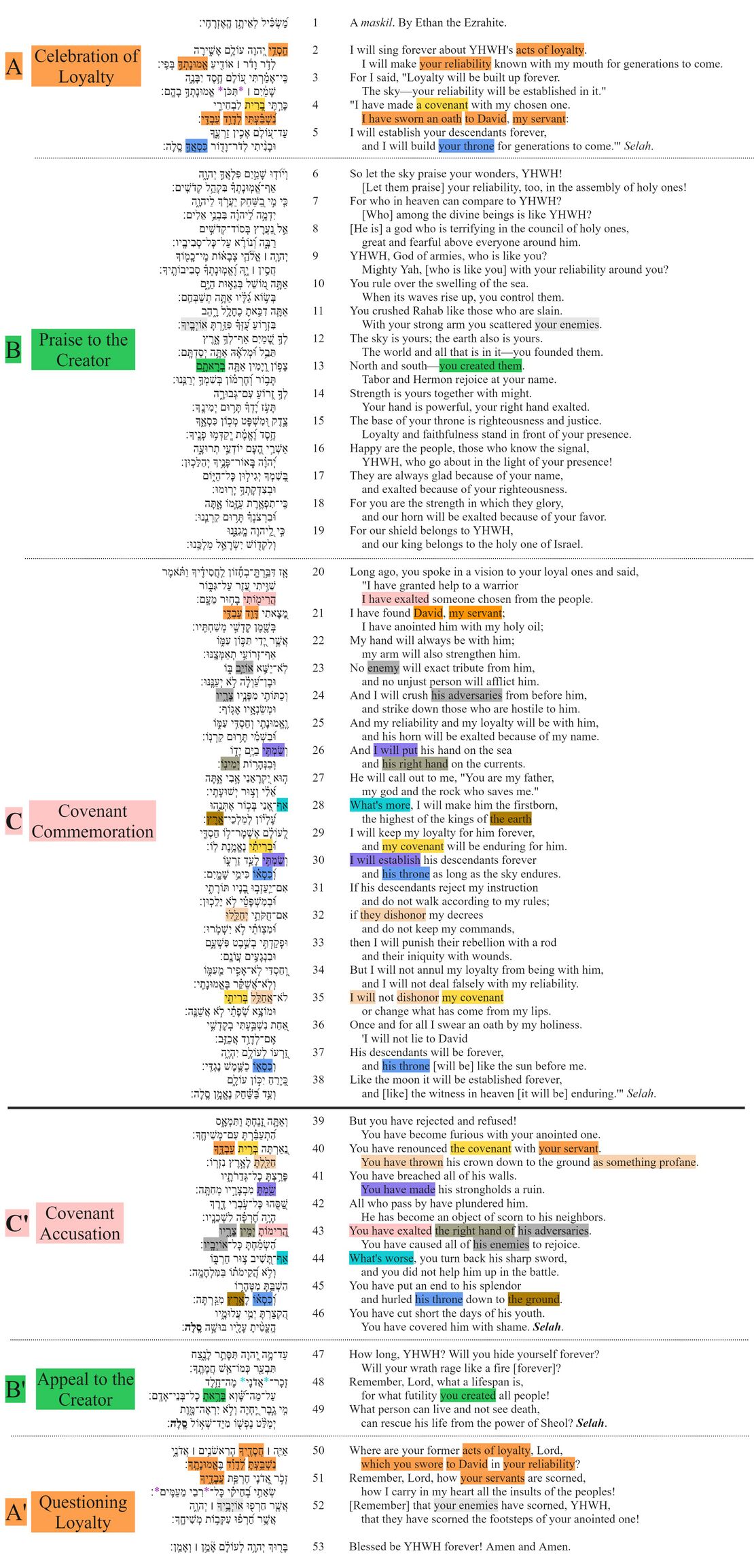

The psalm has two main parts: vv. 2–38 / vv. 39–52, with v. 53 as a conclusion to psalm as a whole and to Book III of the Psalter. It is plausible that the two main parts come from different authors, writing at different points in time, the first part (vv. 2–38) by Ethan the Ezrahite (see v. 1), a contemporary of David who writes in celebration of YHWH's loyalty to David, and the second part (vv. 39–52) by the Korahites (see Ps 88:1), who write at a later point in time in response to YHWH's apparent breach of loyalty with David (see further The Identity of Ethan the Ezrahite in Psalm89:1). According to the 19th century Rabbi Moshe Yitzhak Ashkenazi, Ethan the Ezrahite wrote vv. 2–38, and "afterwards, the Levites sang it in the sanctuary. And in the days of one of the Judahite kings (Hezekiah?) they added to it..." This understanding of the psalm's history admittedly involves some speculation, but it does account well for the superscriptions[1] and for the content of the psalm itself (which has a strong break between vv. 2–38 and vv. 39ff). Nevertheless, even if these two parts of the psalm come from different authors, they have now been integrated into a single poem (see especially the repetition of key words from vv. 2–5 in v. 50). Perhaps the second part (vv. 39–52) was written as a direct poetic response to the first part, the original poem (vv. 2–38).[2]

- The first part of the psalm (vv. 2–38) has a clear ABAB structure. The first A-B unit is vv. 2–5 (A = vv. 2–3; B = vv. 4–5). This unit briefly introduces the main themes and genres of the psalm and anticipates the movement of the psalm as a whole (A = praise to YHWH, psalmist as speaker; B = YHWH's covenant with David, YHWH as speaker). The second A-B unit is vv. 6–38 (A = vv. 6–19; B = 20–38) and it develops what was briefly introduced in the first A-B unit. Each A-B unit concludes with Selah.

- A (vv. 2–3). Praise to YHWH (psalmist as speaker) (genre: praise).

- B (vv. 4–5). YHWH's covenant with David (YHWH as speaker) (genre: prophecy), ending in Selah.

- A (vv. 6–19). Praise to YHWH (psalmist as speaker) (genre: praise).

- B (vv. 20–38). YHWH's covenant with David (YHWH as speaker) (genre: prophecy), ending in Selah.

- The first A-B (vv. 2–5) unit functions as an introduction to the psalm and to vv. 6–38 in particular. This opening unit is bound by the repetition of the words "build" and "establish" and the phrase "for generations to come."

- The second A-B unit (vv. 6–38) is considerably longer than the first and constitutes the main body of the poem. It is bound by an inclusio (the phrase "in heaven").

- The "A" section (vv. 6–19) of this larger unit is bound by an inclusio ("holy one," "to YHWH"). This section subdivides into three sub-sections (vv. 6–9; vv. 10–15; vv. 16–19), and each of these subsections further divides into smaller sub-sections.

- The "B" section (vv. 20–38) of this larger unit subdivides into two subsections (vv. 20–28; vv. 29–38), the latter of which is bound by an inclusio (note esp. the words "forever" and "enduring" that begin and end the section respectively). These sections divide further into smaller subsections.

- The second main part of the psalm (vv. 39–52) is bound by an inclusio ("your anointed one"). This part consists of two sections: vv. 39–46, concluding with Selah, and vv. 47–52.[3]

- The first of these sections (vv. 39–46) is dominated by 2ms indicative verbs, describing YHWH's breach of covenant loyalty. There might also be a chiasm here: a. end of kingdom (vv. 39–40) ("to the ground"); b. defeat in battle (vv. 41–42); b. defeat in battle (vv. 43–44); a. end of kingdom (vv. 45–46) ("to the ground").

- The second of these sections (vv. 47–52) has an ABC//ABD structure. A = question ("how long?" // "where?") + vocative; B = "Remember, Lord...!"

- Verse 53 is a conclusion to the whole psalm as well as a conclusion to Book III of the Psalter (cf. the conclusion to Pss 41; 72; 106).

At the highest structural level, the analysis here agrees largely with structure proposed by Baethgen and others:[4] an introduction (vv. 2–5) followed by three main parts (vv. 6–19; vv. 20–38; vv. 39–52). But we would nuance this description as follows: an introduction (A-B: vv. 2–5) followed by two main parts (A: vv. 6–19; B: vv. 20–38), followed, at a later stage, by another main part (vv. 39–52).

Van der Lugt sees "three main sections which are clearly distinguished from each other on the basis of their individuality in terms of literary genre: vv. 2–19 (a hymn of praise), 20–38 (a divine oracle) and 39–52 a complaint."[5] But vv. 2–19 are not purely a "hymn of praise." Rather, these verses include a "divine oracle" within them (vv. 4–5). It is better to see vv. 2–5 as consisting of two parts (A: praise; B: divine oracle), which anticipate the next major two parts of the psalm: the hymn of praise (A: vv. 6–19) and the divine oracle (B: vv. 20–38). This division also better accounts for the occurrence of selah.

Veijola sees a different three-part structure, arguing that the present psalm was composed in three stages: (1) a hymn (vv. 2–3, 6–19); (2) a longer poem about YHWH's covenant with David and its apparent violation (4–5, 20–46); and (3) a petition for YHWH to remember.[6] But this hypothesis fails to account for the inclusio ("your anointed one") that binds vv. 39–52,[7] as well as the strong unity of vv. 2–38 and, in particular, vv. 6–38.[8]

Line Divisions

Line division divides the poem into lines and line groupings. We determine line divisions based on a combination of external evidence (Masoretic accents, pausal forms, manuscripts) and internal evidence (syntax, prosodic word counting and patterned relation to other lines). Moreover, we indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing.

When line divisions are uncertain, we consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. Then, if a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences our decision to divide the text at a certain point, we place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

| Poetic line division legend | |

|---|---|

| Pausal form | Pausal forms are highlighted in yellow. |

| Accent which typically corresponds to line division | Accents which typically correspond to line divisions are indicated by red text. |

| | | Clause boundaries are indicated by a light gray vertical line in between clauses. |

| G | Line divisions that follow Greek manuscripts are indicated by a bold green G. |

| DSS | Line divisions that follow the Dead Sea Scrolls are indicated by a bold green DSS. |

| M | Line divisions that follow Masoretic manuscripts are indicated by a bold green M. |

| Number of prosodic words | The number of prosodic words are indicated in blue text. |

| Prosodic words greater than 5 | The number of prosodic words if greater than 5 is indicated by bold blue text. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

- The line division for this psalm is fairly straightforward. The only difficulties are in vv. 8–9 (discussed in Grammar), v. 20, and v. 53.

- The analysis here agrees completely with that of Veijola 1982, 23–26.

- Every verse consists of two lines, except for v. 20, which has three lines, and v. 53, which consists of a single line.

- vv. 8–9. On the line division in vv. 8–9, see grammar notes. The division here follows the Septuagint for both lines.

- v. 20. It is not clear whether וַתֹּ֗אמֶר is part of the preceding line or the following line. (The Septuagint groups it with the following line, and Jerome groups it with the preceding line.) We have grouped it with the preceding line, because (1) it corresponds more closely with this line semantically ("you spoke... and said"), and (2) this division results in a nice balanced parallel between v. 20b and v. 20c, (eight syllables // eight syllables), which are semantically similar. (In this case, the relation of the accents to the line division is not clear. For the revia over וַתֹּ֗אמֶר, we might have expected ole we-yored.)

- v. 53. The Leningrad Codex (according to BHS and OSHB) reads לְ֝עוֹלָ֗ם. The accent here is revia muggrash. The Aleppo Codex has revia without the geresh (= revia replacing atnach),[9] which is what we would expect in this situation.[10] If we follow the Aleppo Codex and remove the geresh, then we would mark the accent on לְעוֹלָ֗ם as indicating a line division (cf. the line division in EC1 above). The Septuagint (according to the manuscript tradition [e.g., S, B, A, 1219, 2039, 2110] and not according to Rahlfs' edition) presents v. 53 as a single line.

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

Like Father, Like Son

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

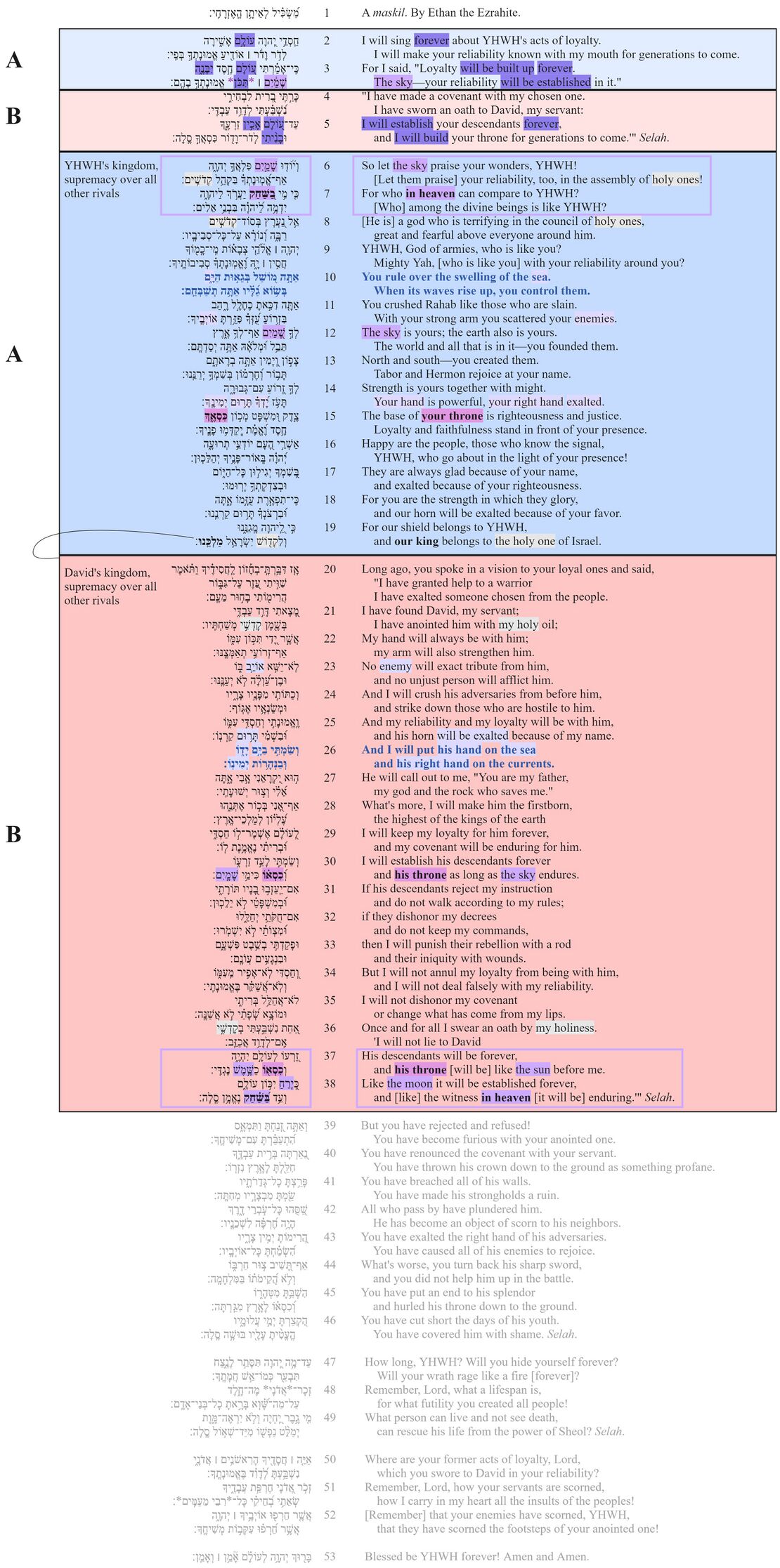

The first major part of the psalm (vv. 2–38) has an ABAB structure (see Poetic Structure). The first AB section (vv. 2–5) functions as an introduction to the second, longer AB section (vv. 6–38), which functions as the main body of the poem.

The A sections differ significantly from the B sections, even leading some scholars to conclude that they were originally separate poems that an editor has blended together in an alternating ABAB sequence (e.g., Gunkel 1926; Sarna 2000). The "A" sections (vv. 2–3, vv. 6–19) feature the psalmist's voice, giving praise to YHWH, while the "B" sections (vv. 4–5, vv. 20–38) feature YHWH's voice, making a covenant with David.

Despite the differences in speaker and genre, the A and B sections of the psalm are highly integrated.

- The first AB unit (vv. 2–5) is integrated by the repetition of the words "build," "establish," and "forever."

- The second AB unit (vv. 6–38) is integrated by numerous repeated words, themes, and images. Repeated words and roots include, most notably, "sea" (vv. 10, 26), "enemy" (vv. 11, 23), "exalted" (vv. 14, 25), "hand"/"right hand" (vv. 14, 26), "throne" (vv. 15, 30), "holy" (קדשׁ) (vv. 6, 8, 19, 20, 36), and the rare phrase "in heaven" (vv. 7, 38) that frames the entire unit. The most notable repeated image is control over the sea in vv. 10, 26. Thematically, both halves of the second AB section (vv. 6–38) are about kingship and supremacy over rivals.

- Furthermore, the last word of the second A unit is "our king" (v. 19) which anticipates the second B unit (vv. 20ff).

Effect

The poet never explicitly spells out the connection between the A sections and the B sections (though v. 19b comes close to doing so). Instead, he expects his readers to carefully ponder the connections across the disparate parts. He has skillfully put the A and B sections together, and it is the reader's job to figure out why.

At least two messages might be drawn from the connections.

The first is that David's kingdom is a reflection and earthly manifestation – perhaps even an incarnation – of YHWH's kingdom. Just as YHWH is supreme among the heavenly beings (vv. 6–8), so David is the "highest of the earthly kings" (v. 28), and just as YHWH controls the sea (a symbol of chaos and enemies) (vv. 10–11), so he puts David's hand on the sea (v. 26). In other words, the royal "son" represents and resembles his heavenly "father" (cf. v. 27). He manifests the supremacy and dominion of his heavenly father in the earthly realm. As long as YHWH, the father, remains supreme and his kingdom endures, the kingdom of his son, David, will endure and remain supreme (cf. Pss 2, 110).

The second, related, message, is that the same power and reliability that uphold creation (A sections) uphold the covenant with David (B sections). Thus, the "sky," which belongs to YHWH (v. 12) and praises YHWH for his power and reliability (v. 6), is a symbol of David's kingdom (vv. 30, 37) and a witness to the Davidic covenant (v. 38). The prophet Jeremiah draws a similar connection (maybe based on this psalm!): "If you can break my covenant with the day and my covenant with the night, so that day and night will not come at their appointed time, then also my covenant with David my servant may be broken, so that he shall not have a son to reign on his throne" (Jer 33:20–21, ESV).

"You Spoke in a Vision"

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

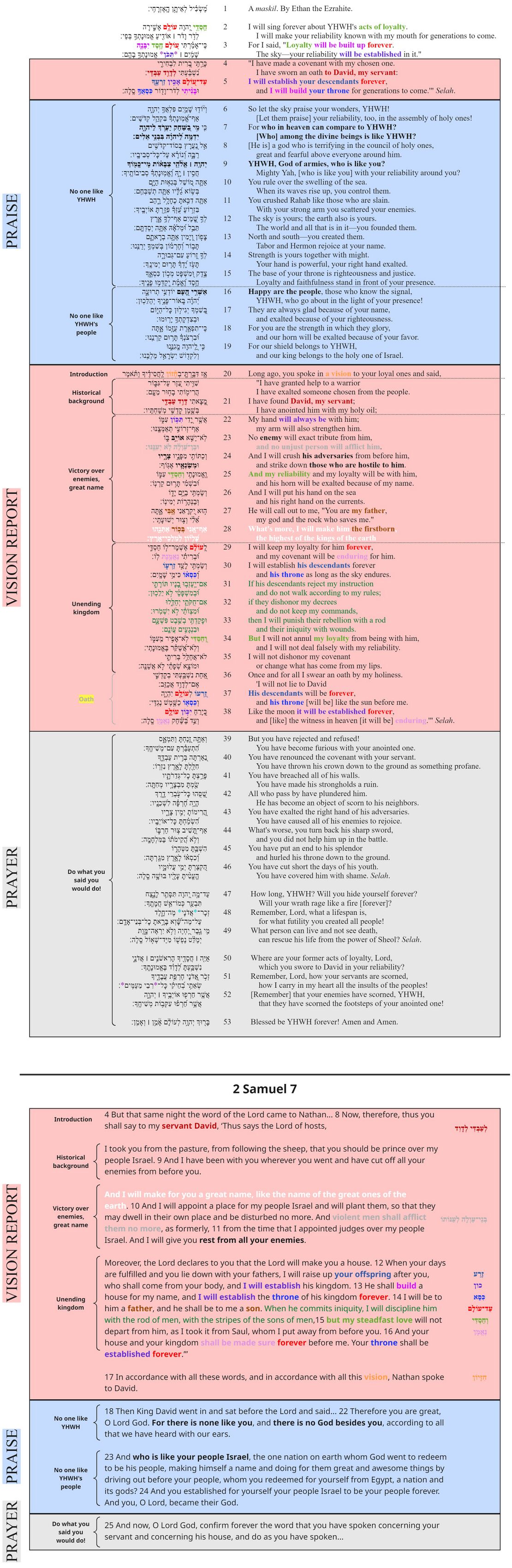

Some of the most repeated words in Psalm 89 include "loyalty" (חֶסֶד), "establish" (כון), "throne" (כִסֵּא), "descendants" (זֶרַע), and "forever" (עוֹלָם). Other repeated words and phrases include "David, my servant" (דָוִד עַבְדִּי), "enduring" (נֶאֱמָן), and "build" (בנה). All of these repeated elements feature prominently in 2 Samuel 7, the primary passage that recounts YHWH's promises to David, revealed in a vision through Nathan the prophet (see also 1 Chr 17).[11]

In addition to these connections at the level of the word, Psalm 89 also echoes 2 Samuel 7 at the level of its discourse structure. In 2 Samuel 7, there is a report of a vision (vv. 4–17), a response of praise (vv. 18–24), and a prayer for YHWH to keep his promises (vv. 25–29). Similarly, Psalm 89 consists of a vision report (vv. 4–5, 20–38), a hymn of praise (vv. 2–3, 6–19), and a plea for YHWH to keep his promises (vv. 39–53). Furthermore, each of these parts within the psalm follows the thematic flow of the corresponding parts in 2 Samuel 7. The vision report in both Psalm 89 and 2 Samuel 7 consists of a historical background, promises of victory over enemies, and promises of an unending kingdom. The praise section in both passages begins by celebrating YHWH's uniqueness and ends by celebrating the uniqueness of YHWH's people. Thus, Psalm 89 not only reflects 2 Samuel 7 in terms of its theme and vocabulary, but also in terms of its structure.

At the same time, there are some notable differences between the two passages.[12] Whereas the temple features prominently in 2 Samuel 7, it does not appear in Psalm 89. Furthermore, Psalm 89 emphasizes the covenantal nature of the promises to David, using the language of "covenant" and "oath," whereas such ideas are left implicit in 2 Samuel 7 (cf. 2 Sam 23:5; 2 Chr 13:5; Ps 132:11–12; Isa 55:3; Jer 33:17, 21).

Effect

Psalm 89 is "an exegetical adaptation" of the oracle to Nathan the prophet as narrated in 2 Samuel 7.[13] Therefore, recognizing the oracle in 2 Samuel 7 as the background of Psalm 89 is crucial for truly understanding and appreciating the psalm. To a large extent, recognizing the connections to 2 Samuel unlocks the rationale behind the psalm's structure and choice of key words. The whole poem has grown out of this earlier oracle, as an elaboration on it, a celebration of it, and a direct response to it.

Recognizing the oracle in 2 Samuel 7 as the background to Psalm 89 also helps us to see what is foregrounded in the psalm. For example, whereas Psalm 89 turns down the volume on the temple theme in 2 Samuel 7,[14] it amplifies the covenantal nature of the promises found in that passage. Psalm 89 also includes an oath (not explicit in 2 Sam 7, though perhaps implied), as YHWH swears by his holiness to keep the covenant forever (vv. 36–38). The moon, evidence of YHWH's covenant faithfulness over all creation (cf. Gen 8:22; Jer 33:20–21), is invoked as a witness to this oath (cf. 2 Sam 7:4: "on that night"). By foregrounding these elements, the psalm emphasizes the unbreakable nature of the promises, sealed with an oath.

A Poetic Response

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

The last major section of the psalm (vv. 39–53) was probably written as a poetic response to vv. 1–38, which existed as an independent psalm (see Poetic Structure). This final section is structured in three parts, according to the use of Selah (vv. 46, 49; see Poetic Structure for more poetic structural markers). The first major part of the psalm (vv. 1–38) also consists of three major sections (vv. 1–5; vv. 6–19; vv. 20–38; see Poetic Structure).

There are numerous linguistic and thematic connections between each of the three sections in vv. 39–53 (the response) and each of the three sections in vv. 1–38 (the originally independent poem).

Verses 39–46 (C') have numerous connections to vv. 20–38 (C)[15]

- "covenant with your servant" (v. 40 --> vv. 21, 35)

- "profane" (v. 40 --> vv. 32, 35)

- "you have made" (v. 41 --> vv. 26, 30)

- "you have exalted the right hand of his adversaries" (v. 43 --> vv. 20, 23–24, 26) (the only two occurrences of hiphil הרים in the psalm)

- "What's worse" (v. 44 --> v. 28)

- "throne to the ground (v. 45 –-> vv. 28, 37)

Verses 47–49 (B') have a significant lexical and thematic connection to vv. 6–19 (B).

- "you created" (v. 48 --> v. 13). (The verb ברא is relatively rare, occurring only six times in the Psalter, two of which are in this psalm.)

- appeal to YHWH's identity as creator of all people (vv. 47–49 --> vv. 10–15).

Verses 50–53 (A') have numerous lexical connections to vv. 1–5 (A).

- "acts of loyalty, which you swore to David in your reliability" )" (v. 50 --> vv. 2, 4) (the only two occurrences of חסדים [plural] in the psalm)

- "your servants" (v. 51 --> v. 4)

Effect

Structurally, the repetitions create a chiasm (ABC//C'B'A').

A: Celebration of Loyalty (vv. 1–5) B: Praise to the Creator (vv. 6–19) C: Covenant Commemoration (vv. 20–38) C': Covenant Accusation (vv. 39–46) B': Appeal to the Creator (vv. 47–49) A': Questioning Loyalty (vv. 50–53)

The response (vv. 39–53) thus mirrors the original poem (vv. 1–38).

The lexical and thematic repetitions also give rhetorical force to the psalmist's response in vv. 39–53. The "Covenant Accusation" (C') section (vv. 39–46) is a direct response to the "Covenant Commemoration (C) section, which presents the Davidic covenant (vv. 20–38). The psalmist says, in effect, "You did not do the things you said you would do. In fact, you have done the opposite! The very things you said you would do for David, you have done against him and for his enemies!"

Then, in the "Appeal to the Creator" (B') section (vv. 47–49), the psalmist appeals to YHWH's mercy as creator. The appeal is based on the description in the "Praise to the Creator" (B) section (vv. 6–19). Working backwards through the original psalm, there is reason for hope.

Finally, in the "Questioning Loyalty" (A') section (vv. 50–53), the psalmist appeals to YHWH's oath to David and to his "former acts of loyalty." The appeal is based on the "Celebration of Loyalty" (A) section (vv. 2–5), which affirmed that YHWH's loyalty would continue forever.

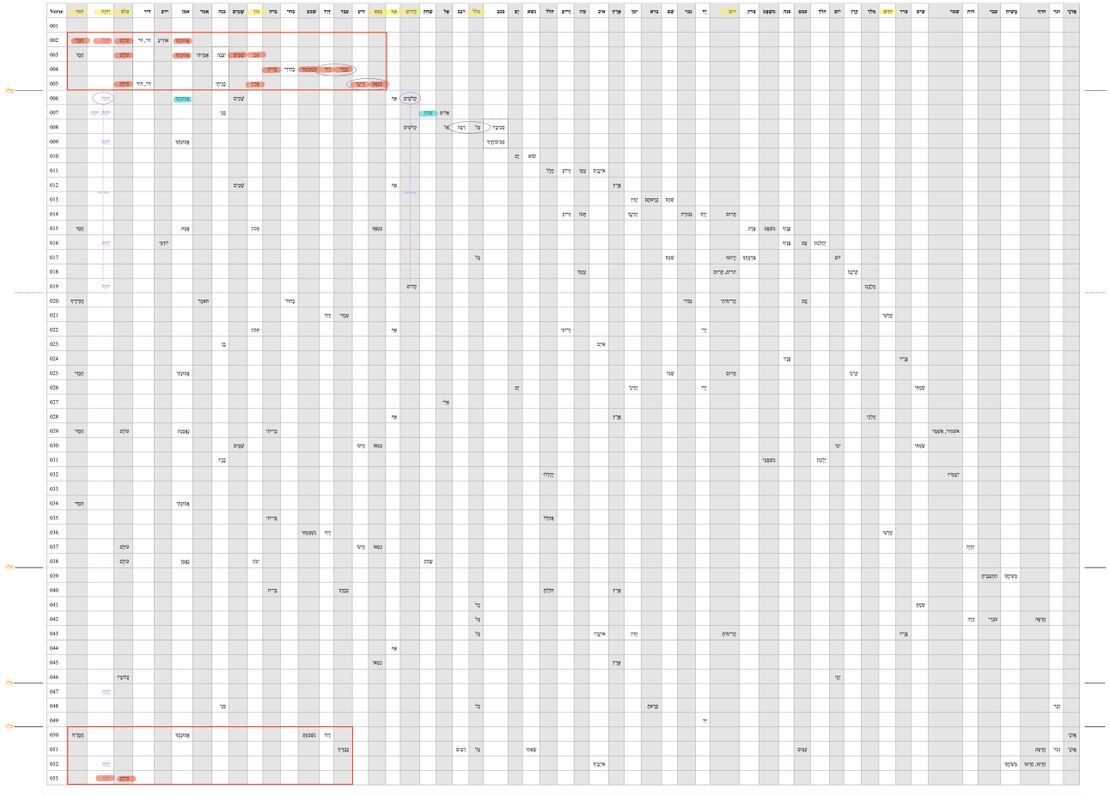

Repeated Roots

The repeated roots table is intended to identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm.

| Repeated Roots legend | |

|---|---|

| Divine name | The divine name is indicated by bold purple text. |

| Roots bounding a section | Roots bounding a section, appearing in the first and last verse of a section, are indicated by bold red text. |

| Roots occurring primarily in the first section are indicated in a yellow box. | |

| Roots occurring primarily in the third section are indicated in a blue box. | |

| Roots connected across sections are indicated by a vertical gray line connecting the roots. | |

| Section boundaries are indicated by a horizontal black line across the chart. | |

Bibliography

- Andrason, Alexander. 2012. “Making It Sound - The Performative Qatal and Its Explanation.” The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 12.

- Avalos, Hector. 1992. “Zaphon, Mount.” In Anchor Bible Dictionary. Doubleday.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Ballentine, Debra Scoggins. 2012. “‘You Divided Sea by Your Might’: The ‘Conflict Myth’ and the Biblical Tradition.” Ph.D, Brown University.

- Bandstra, Barry. 1995. “Marking Turns in Poetic Text. ‘Waw’ in the Psalms.” Narrative and Comment: Contributions to Discourse Grammar and Biblical Hebrew, 45–52.

- Barbiero, Gianni. 2007. “Alcune osservazioni sulla conclusione del salmo 89 (vv. 47-53).” Biblica 88 (4): 536–45.

- Barthélemy, Dominique, Norbert Lohfink, Alexander R. Hulst, William D. McHardy, H. Peter Rüger, and James A. Sanders. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament 4: Psaumes. Edited by Stephen Desmond Ryan and Adrian Schenker. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis, 50,4. Academic Press.

- Bekins, Peter. 2017. “Definiteness and the Definite Article.” In “Where Shall Wisdom Be Found?”: A Grammatical Tribute to Professor Stephen A. Kaufman, edited by Hélène Dallaire, Benjamin J. Noonan, Jennifer E. Noonan, and Stephen A. Kaufman. Eisenbrauns.

- Brockington, L.H. 1973. The Hebrew Text of the Old Testament: The Readings Adopted by the Translators of the New English Bible.

- Calvin, John. 1847. Commentary on the Book of Psalms. Translated by James Anderson. Vol. 1. Calvin Translation Society.

- Cook, John A. 2024. The Biblical Hebrew Verb: A Linguistic Introduction. Learning Biblical Hebrew. Baker Academic.

- Dahood, Mitchell J. 1968. Psalms II, 51-100: Introduction, Translation, and Notes. Anchor Bible 17. Doubleday.

- Day, John. 2020. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea: Echoes of a Canaanite Myth in the Old Testament. Reprint of the 1988 corrected edition. Wipf & Stock.

- Delitzsch, F. 1996. “The Psalter.” In Commentary on the Old Testament. Hendrickson.

- Eaton, J.H. 1975. Kingship and the Psalms. Studies in Biblical Theology Second Series 32. SCM Press.

- Ellison, D. 2024. “Singing Steadfast Love and Faithfulness: The Messianic Significance of Psalm 89.” Old Testament Essays 37 (3): 1–19.

- Frankel, Rafael. 1992. “Tabor.” In Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 6. Doubleday.

- Gentry, Peter J. 1998. “The System of the Finite Verb in Classical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 39: 7–39.

- Gentry, Peter J., and Stephen J. Wellum. 2012. Kingdom Through Covenant: A Biblical-Theological Understanding of the Covenants. Crossway.

- Gesenius, Wilhelm. 2013. Hebräisches und Aramäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament. 18th ed. Edited by Herbert Donner. Springer.

- Goldingay, John. 2007. Psalms: Psalms 42–89;;. Vol. 2. BCOT. Baker Academic.

- Gray, George Buchanan. 1915. The Forms of Hebrew Poetry: Considered with Special Reference to the Criticism and Interpretation of the Old Testament. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Gunkel, Hermann. 1998. An Introduction to the Psalms: The Genres of the Religious Lyric of Israel. Translated by James D. Nogalski. Mercer University Press.

- Hengstenberg, E.W. 1848. Commentary on the Psalms. Translated by J.T. Leith and P.F. Salton. Vol. 3. T&T Clark.

- Hoffmeier, James. 1994. “The King as Son of God in Egypt and Israel.” The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 24: 28–38.

- Holmstedt, Robert D. 2016. The Relative Clause in Biblical Hebrew. Linguistic Studies in Ancient West Semitic 10. Eisenbrauns.

- Hoop, Raymond de, and Paul Sanders. 2022. “The System of Masoretic Accentuation: Some Introductory Issues.” Journal of Hebrew Scriptures 22.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 2005. Psalms 2: A Commentary on Psalms 51-100. Translated by Linda M. Maloney. Hermeneia. Fortress.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1860. Die Psalmen. Vol. 3. F.A. Perthes.

- Huang, JengZen. 2015. “A Quantitative Study of the Vocalization of the Inseparable Prepositions in the Hebrew Bible.” Doctor of Theology, Wycliffe College and the University of Toronto.

- Ibn Ezra. Ibn Ezra on Psalms.

- Irvine, Stuart A. 2019. “The ‘Rock’ of the King’s Sword? A Note on צור in Psalm 89:44.” Vetus Testamentum 69 (4–5): 742–47.

- Jenni, Ernst. 1992. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 1: Die Präposition Beth. W. Kohlhammer.

- Jenni, Ernst. 2000. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Kennicott, Benjamin. 1776. Vetus testamentum hebraicum : cum variis lectionibus.

- Lane, Daniel. 2000. “The Meaning and Use of the Old Testament Term for ‘Covenant’ (Berit): With Some Implications for Dispensationalism and Covenant Theology.” PhD, Trinity International University.

- Liddell, Henry George, and Robert Scott. 1996. A Greek-English Lexicon. Ninth edition. Edited by Henry Stuart Jones. Clarendon press.

- Locatell, Christian. 2019. “Causal Categories in Biblical Hebrew Discourse: A Cognitive Approach to Causal כי.” Journal of Northwest Semitic Languages 45 (2).

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2010. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry II: Psalms 42-89. Vol. 2. Oudtestamentische Studiën 57. Brill.

- Lunn, Nicholas P. 2006. Word-Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: Differentiating Pragmatics and Poetics. Paternoster Biblical Monographs. Paternoster.

- Mays, James Luther. 1994. The Lord Reigns: A Theological Handbook to the Psalms. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Mena, Andrea K. 2012. “The Semantic Potential of עַל in Genesis, Psalms, and Chronicles.” MA Thesis, Stellenbosch University.

- Miller, Cynthia L. 2010. “Vocative Syntax in Biblical Hebrew Prose and Poetry: A Preliminary Analysis.” Semitic Studies 55 (1): 347–64.

- Mullen. 1992. “Divine Assembly.” In Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 2. Doubleday.

- Murnane, William Joseph, and Edmund S. Meltzer. 1995. Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt. Writings from the Ancient World 5. Scholars Press.

- Mussies, G. 1999. “Tabor.” In Dictionary of the Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., edited by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter Willem van der Horst. Brill.

- Niehaus, Jeffrey J. 2008. Ancient Near Eastern Themes in Biblical Theology. Kregel Publications.

- Niehr, H. 1999. “Baal-Zaphon.” In Dictionary of the Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., edited by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter Willem van der Horst. Brill.

- Penney, Jason. 2023. “A Typological Examination of Pluractionality in the Biblical Hebrew Piel.” MA, Dallas International University.

- Pohl, William C. 2015. “A Messianic Reading of Psalm 89: A Canonical and Intertextual Study.” JETS 58 (3): 507–25.

- Sarna, Nahum M. 2000. “Psalm 89. A Study in Inner Biblical Exegesis.” Studies in Biblical Interpretation, 377.

- Poole, Matthew. 1678. Synopsis criticorum aliorumque sacrae scripturae. 2: a Jobi ad Canticum Canticorum. Balthasaris Christophori Wustii.

- Radak. Radak on Psalms.

- Rashi. Rashi on Psalms.

- Röllig, K. 1999. “Hermon.” In Dictionary of the Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., edited by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter Willem van der Horst. Brill.

- Ryken, Leland, Jim Wilhoit, Tremper Longman, Colin Duriez, Douglas Penney, and Daniel G. Reid, eds. 1998. Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. InterVarsity Press.

- Sforno. Rabbi Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno on Psalms.

- Sikes, Ryan. 2025. “Stichography and Stichometry in the Old Greek Psalter.” PhD, Columbia International University.

- Spronk, K. 1999. “Rahab.” In Dictionary of the Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., edited by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter Willem van der Horst. Brill.

- Staszak, Martin. 2024. The Preposition Min. Beiträge zur Wissenschaft vom Alten und Neuen Testament (BWANT) 246. Kohlhammer.

- Stec, David M., ed. 2004. The Targum of Psalms. The Aramaic Bible 16. Liturgical Press.

- Süring, Margit L. 1980. The Horn-Motif in the Hebrew Bible and Related Ancient Near Eastern Literature and Iconography. Andrews University Press.

- Taylor, Richard A. 2020. The Psalms According to the Syriac Peshitta Version with English Translation. Gorgias Press.

- Tsumura, David Toshio. 2020. “Chaoskampf Myth in the Biblical Tradition.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 140 (4).

- Veijola, Timo. 1982. Verheissung in der Krise : Studien zur Literatur und Theologie der Exilszeit anhand des 89. Psalms. Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

- Veijola, Timo. 1988. “The Witness in the Clouds: Ps 89:38.” Journal of Biblical Literature 107 (3): 413–17.

- Walton, John H. 2018. Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. 2nd edn. Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group.

- Walton, John H. 2011. Genesis 1 as Ancient Cosmology. Eisenbrauns.

- Ward, James M. 1961. “The Literary Form and Liturgical Background of Psalm LXXXIX.” Vetus Testamentum 11 (3): 321–39.

- Witthoff, David J. 2021. "The Relationships of the Senses of נֶפֶשׁ in the Hebrew Bible: A Cognitive Linguistics Perspective". PhD Dissertation, University of Stellenbosch.

- Wolde, Ellen van. 2019. “Accusing YHWH of Fickleness.” Biblica, no. 4: 506–26.

Footnotes

- ↑ Ps 89:1 and Ps 88:1 (which has a double superscription, the first of which stands over Pss 88–89 as a unit, so Hengstenberg).

- ↑ On the unity of the present poem, see e.g., Ward 1961.

- ↑ Cf. van Wolde 2019.

- ↑ Baethgen 1904, 274; see also Pohl 2015.

- ↑ Van der Lugt 2010, 474; so also Hossfeld and Zenger 2000, 406–407; Ellison 2024, 5.

- ↑ Veijola 1982, 47–52.

- ↑ So van der Lugt 2010, 477.

- ↑ On the difficulty of separating vv. 47–52 from the rest of the poem, see Barbiero 2007.

- ↑ Cf. Ginsburg 1913, 199.

- ↑ See Yeivin 1980, #363; de Hoop and Sanders 2022, §6.2.

- ↑ For a full list of lexical connections between Ps 89 and 2 Sam 7, see Veijola 1982, 48–49.

- ↑ Cf. Sarna 2000.

- ↑ Sarna 2000, 39.

- ↑ Cf. Sarna 2000.

- ↑ So Veijola 1988, 417.