Psalm 8 Discourse

About the Discourse Layer

Our Discourse Layer includes four additional layers of analysis:

- Participant analysis

- Macrosyntax

- Speech act analysis

- Emotional analysis

For more information on our method of analysis, click the expandable explanation button at the beginning of each layer.

Participant Analysis

Participant Analysis focuses on the characters in the psalm and asks, “Who are the main participants (or characters) in this psalm, and what are they saying or doing? It is often helpful for understanding literary structure, speaker identification, etc.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Participant Analysis Creator Guidelines.

There are 5 participants/characters in Psalm 8:

Profile List

| David |

| "David" (v. 1) |

| YHWH |

| "YHWH" (vv. 2, 10) |

| "our lord" (vv. 2, 10) |

| Humanity |

| "nursing children" (v. 3) |

| "mankind" (v. 5) |

| "human being" (v. 5) |

| Enemies |

| "adversaries" (v. 3) |

| "vengeful enemy" (v. 3) |

| Animals |

| "sheep" (v. 8) |

| "goats and cattle" (v. 8) |

| "wild animals" (v. 8) |

| "birds" (v. 9) |

| "fish" (v. 9) |

Profile Notes

- David: David, the 10th century king of Israel and Judah, is named in the superscription (v. 1) as the author of the psalm. The fact that the psalm was written by a king is significant. Behind the psalm's reflection on humanity, there is an implicit reflection on David's kingdom and dynasty. David, the shepherd boy and the youngest of his brothers, was an unlikely candidate for the throne (cf. v. 5). Nevertheless, YHWH exalted him and gave him dominion over his enemies (cf. vv. 6–9).

- YHWH:The psalm is addressed to "YHWH" (vv. 2, 10), the God of Israel and the creator and "Lord" of the world. The entire psalm is addressed to YHWH in the second person. "It is worth stressing that throughout the entire poem, the Creator is addressed directly and intimately: your name, you have established, your heavens, you remember them, and so on."[1]

- Nursing children (עוֹלְלִים וְיֹנְקִים) (v. 3) represent the weakest and most vulnerable part of the human race (cf. 1 Sam 15:3; 22:29; Jer 44:7; Lam 1:16; Joel 2:16). They are an image of Israel and her kings, who were completely dependent on YHWH for help. Their best hope was to cry out to him.

- YHWH's enemies (v. 3) may be either "historical persons and nations (Ps 2:1-3) or mythological beings and disruptive cosmic forces (Pss 74:13; 89:10; 93:3)."[2] Those who argue for the latter think that "the enemy and avenger in v. [3]c are best explained as a reference to the foes that God overcomes in the process of creation."[3] Those who argue that the adversaries are human and historical point to the use of the phrase "your adversaries" (צֹרְרֶיךָ) in Ps 74:4 and "vengeful enemy" (אויב ומתנקם) in Ps 44:17 to refer to Israel's enemies[4] along with the fact that "here, as throughout the psalms, the psalmist is fluidly able to identify personal enemies with those hostile to God."[5] This view is probably correct, and the enemies probably refer to the enemies of God's people.

- Animals: Vv. 8-9 lists three basic categories of animals: (1) land animals, domestic and wild (v. 8), (2) birds (v. 9aα), and (3) fish (v. 9aβb). The list of animals in these verses illustrate the "horizontal vector that moves outward from human society: sheep and oxen → beasts of the field → birds → fish → whatever passes the paths of the seas."[6] There is a subtle connection between the "enemies" whom YHWH defeats (v. 3) and the "animals" which YHWH subjugates under humanity's feet (vv. 8–9). Elsewhere, wild animals are used to depict the enemies of God's people (e.g., Pss 7:3; 10:9; 17:12; 22:13, 17, 22; 68:30; 80:14,[7] and the image of being put "under one's feet" evokes the conquest of enemies (cf. Josh 10:24; Ps 110:1). The point of the connection is not to say that animals are somehow morally on par with YHWH's wicked enemies. It is to say, however, that they represent a force of chaos that must be subdued.

| Hebrew | Line | English |

|---|---|---|

| לַמְנַצֵּ֥חַ עַֽל־הַגִּתִּ֗ית מִזְמ֥וֹר לְדָוִֽד׃ | 1 | For the director. On the gittith. A psalm by David. |

| יְהוָ֤ה אֲדֹנֵ֗ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֣יר שִׁ֭מְךָ בְּכָל־הָאָ֑רֶץ | 2a | YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth, |

| אֲשֶׁ֥ר תְּנָ֥ה ה֝וֹדְךָ֗ עַל־הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃ | 2b | you whose glory is bestowed on the heavens. |

| מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֨ים ׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֮ יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז | 3a | Out of the mouths of nursing children, you have founded a fortress, |

| לְמַ֥עַן צוֹרְרֶ֑יךָ | 3b | because of your adversaries, |

| לְהַשְׁבִּ֥ית א֝וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם׃ | 3c | in order to put an end to a vengeful enemy. |

| כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶ֣ה שָׁ֭מֶיךָ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י אֶצְבְּעֹתֶ֑יךָ | 4a | When I see your heavens, that which your fingers made, |

| יָרֵ֥חַ וְ֝כוֹכָבִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה׃ | 4b | moon and stars which you have established, |

| מָֽה־אֱנ֥וֹשׁ כִּֽי־תִזְכְּרֶ֑נּוּ | 5a | what is mankind that you should consider them, |

| וּבֶן־אָ֝דָ֗ם כִּ֣י תִפְקְדֶֽנּוּ׃ | 5b | or a human being, that you should be mindful of him? |

| וַתְּחַסְּרֵ֣הוּ מְּ֭עַט מֵאֱלֹהִ֑ים | 6a | And you caused him to lack being a heavenly being by a little, |

| וְכָב֖וֹד וְהָדָ֣ר תְּעַטְּרֵֽהוּ׃ | 6b | and you crowned him with honor and majesty. |

| תַּ֭מְשִׁילֵהוּ בְּמַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָדֶ֑יךָ | 7a | You caused him to rule that which your hands made. |

| כֹּ֝ל שַׁ֣תָּה תַֽחַת־רַגְלָֽיו׃ | 7b | You placed everything under his feet. |

| צֹנֶ֣ה וַאֲלָפִ֣ים כֻּלָּ֑ם | 8a | Sheep and goats and cattle all of them, |

| וְ֝גַ֗ם בַּהֲמ֥וֹת שָׂדָֽי׃ | 8b | and even wild animals, |

| צִפּ֣וֹר שָׁ֭מַיִם וּדְגֵ֣י הַיָּ֑ם | 9a | birds in the sky and fish in the sea, |

| עֹ֝בֵ֗ר אָרְח֥וֹת יַמִּֽים׃ | 9b | that which traverses the paths of the sea. |

| יְהוָ֥ה אֲדֹנֵ֑ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֥יר שִׁ֝מְךָ֗ בְּכָל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃ | 10 | YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth. |

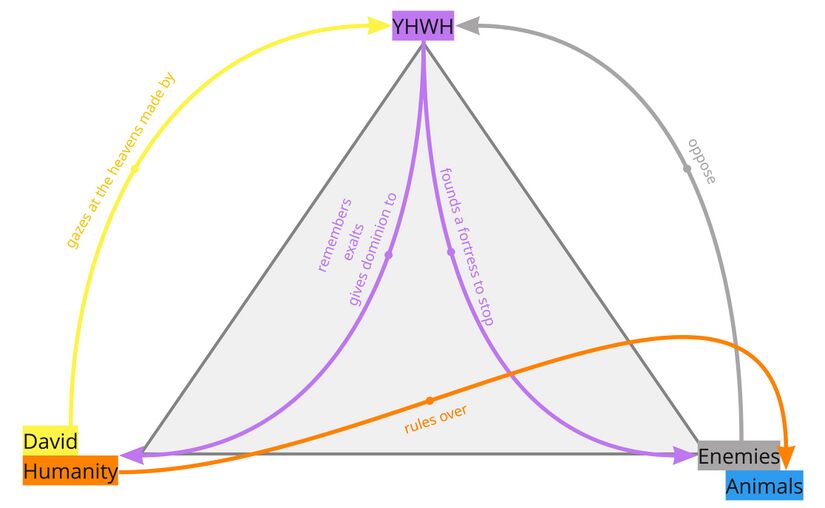

Participant Relations Diagram

The relationships among the participants may be abstracted and summarized as follows:

Macrosyntax

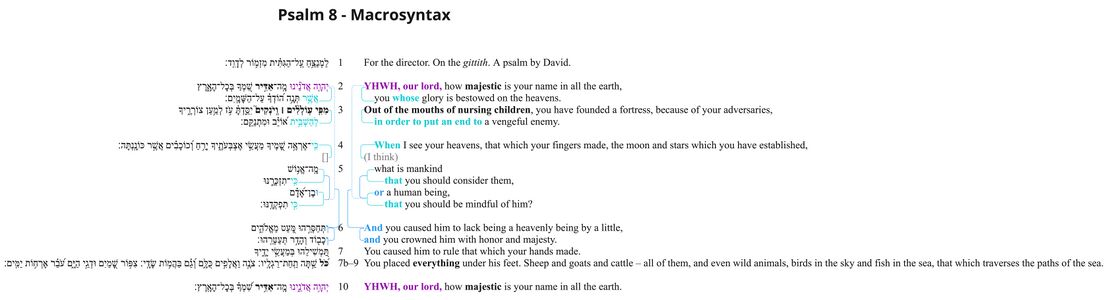

Macrosyntax Diagram

| Macrosyntax legend | |

|---|---|

| Vocatives | Vocatives are indicated by purple text. |

| Discourse marker | Discourse markers (such as כִּי, הִנֵּה, לָכֵן) are indicated by orange text. |

| The scope governed by the discourse marker is indicated by a dashed orange bracket connecting the discourse marker to its scope. | |

| The preceding discourse grounding the discourse marker is indicated by a solid orange bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Subordinating conjunction | The subordinating conjunction is indicated by teal text. |

| Subordination is indicated by a solid teal bracket connecting the subordinating conjunction with the clause to which it is subordinate. | |

| Coordinating conjunction | The coordinating conjunction is indicated by blue text. |

| Coordination is indicated by a solid blue line connecting the coordinating clauses. | |

| Coordination without an explicit conjunction is indicated by a dashed blue line connecting the coordinated clauses. | |

| Marked topic is indicated by a black dashed rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| The scope of the activated topic is indicated by a black dashed bracket encompassing the relevant clauses. | |

| Marked focus or thetic sentence | Marked focus (if one constituent) or thetic sentences[8] are indicated by bold text. |

| Frame setters[9] are indicated by a solid gray rounded rectangle around the marked words. | |

| [blank line] | Discourse discontinuity is indicated by a blank line. |

| [indentation] | Syntactic subordination is indicated by indentation. |

| Direct speech is indicated by a solid black rectangle surrounding all relevant clauses. | |

| (text to elucidate the meaning of the macrosyntactic structures) | Within the CBC, any text elucidating the meaning of macrosyntax is indicated in gray text inside parentheses. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

- v. 1: Superscription

- vv. 2-3. The use of a vocative marks this unit.

- vv. 4-5 are bound together as a syntactic unit. Verse 4 is the protasis, verse 5 the apodosis. The temporal כִּי in v. 4 begins a new paragraph.

- vv. 6-9. The distribution of second person verb forms in vv. 6-7 (wayyiqtol, yiqtol, yiqtol, qatal) binds these clauses together as a unit. Vv. 8-9 are in apposition to כֹּל (v. 7b) and are thus part of the same macrosyntactic unit.

- v. 10. The cessation of appositional phrases and the use of a vocative marks a new macrosyntactic unit.

- vv. 2, 10. The unmarked word order of verbless clauses is Subject-Predicate.[10] The use of interrogative>exclamatory מה and the consequent fronting of the predicate adjective (אַדִּיר) means that the predicate is probably marked.[11] The particle ma "functions as an introduction to an exclamation in which a speaker usually expresses a value judgment about something."[12]

- v. 3a. The PP מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֨ים ׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֮ is fronted for marked focus (Lunn 2006:296 – "MKD"). YHWH has founded a fortress not by means of the powerful and eloquent, but by means of the feeble cries of the weakest and most vulnerable.

- v. 7b. The direct object "everything" (כֹּל) is fronted for marked focus.[13] YHWH has subjected everything to humanity's rule; no creature has been excluded. On the significance of this word in the psalm, see repeated roots.

- vv. 8-9. For the numerous and complex appositional relationships in this verse, see the grammatical diagram.

- v. 3a. "לְמַעַן is a subordinating conjunction that is also used secondarily as a preposition" (BHRG 40.36). In this clause, where is governs only a NP, it functions as a preposition (see grammatical diagram). "The clause or noun phrase with לְמַעַן typically follows the matrix clause" (BHRG 40.36).

- v. 4a. Despite the agreement among the ancient translators that the כִּי in v. 4 is causal (LXX [οτι], Symmachus [γαρ], Peshitta [ܡܛܠ], Targum [מטול], Jerome [enim]), there is virtual unanimity among modern translations and commentators that כי here introduces a temporal clause: "When I see... [then I think/exclaim] what is mankind...?"[14]

- v. 5. On מה followed by כי followed by yiqtol, cf. 1 Sam 18:18. "A result clause can be introduced by כי, notably after a question."[15]

- v. 6a. On the wayyiqtol see notes on verbal semantics.

Speech Act Analysis

The Speech Act layer presents the text in terms of what it does, following the findings of Speech Act Theory. It builds on the recognition that there is more to communication than the exchange of propositions. Speech act analysis is particularly important when communicating cross-culturally, and lack of understanding can lead to serious misunderstandings, since the ways languages and cultures perform speech acts varies widely.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Speech Act Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Summary Visual

| SPEAKER | VERSES | SPEECH ACT SECTIONS | ADDRESSEE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| David | YHWH | |||||

| v. 2 YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth, you whose glory is bestowed on the heavens. |

PRAISE

|

|||||

| v. 3 Out of the mouths of nursing children, you have founded a fortress, because of your adversaries, in order to put an end to a vengeful enemy. |

MARVELLING

|

|||||

| v. 4 When I see your heavens, that which your fingers made, the moon and stars which you have established, | ||||||

| v. 5 what is mankind that you should consider them, or a human being, that you should be mindful of him? | ||||||

| v. 6 And you caused him to lack being a heavenly being by a little, and you crowned him with honor and majesty. | ||||||

| v. 7 You caused him to rule that which your hands made. You placed everything under his feet. | ||||||

| v. 8 Sheep and goats and cattle – all of them, and even wild animals, | ||||||

| v. 9 birds in the sky and fish in the sea, that which traverses the paths of the sea. | ||||||

| v. 10 YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth. |

PRAISE

|

|||||

Speech Act Analysis Chart

The following chart is scrollable (left/right; up/down).

| Verse | Hebrew | CBC | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) |

| Verse number and poetic line | Hebrew text | English translation | Declarative, Imperative, or Interrogative Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

Assertive, Directive, Expressive, Commissive, or Declaratory Indirect Speech Act: Mismatch between sentence type and illocution type |

More specific illocution type with paraphrased context | Illocutionary intent (i.e. communicative purpose) of larger sections of discourse These align with the "Speech Act Summary" headings |

What the speaker intends for the address to think | What the speaker intends for the address to feel | What the speaker intends for the address to do |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| Verse | Text (Hebrew) | Text (CBC) | Sentence type | Illocution (general) | Illocution with context | Macro speech act | Intended perlocution (Think) | Intended perlocution (Feel) | Intended perlocution (Do) | Speech Act Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | לַמְנַצֵּ֥חַ עַֽל־הַגִּתִּ֗ית מִזְמ֥וֹר לְדָוִֽד׃ | For the director. On the gittith. A psalm by David. | ||||||||

| 2 | יְהוָ֤ה אֲדֹנֵ֗ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֣יר שִׁ֭מְךָ בְּכָל־הָאָ֑רֶץ | YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth, | Interrogative | Expressive | Praising YHWH for his majesty | Praising YHWH for his majesty | People who hear the psalm will reflect on what it means to be human and what it means for YHWH to be majestic | YHWH will be pleased with David's praise. People who hear the psalm will be amazed at YHWH's majesty |

People who hear the psalm will marvel at YHWH's majesty | Interrogative מה "functions as an introduction to an exclamation in which a speaker usually expresses a value judgment about something" (BHRG 42.3.6). |

| אֲשֶׁ֥ר תְּנָ֥ה ה֝וֹדְךָ֗ עַל־הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃ | you whose glory is bestowed on the heavens. | Declarative | Assertive | |||||||

| 3 | מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֨ים ׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֮ יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז | Out of the mouths of nursing children, you have founded a fortress, | Declarative | Assertive | Describing (with a metaphor) how YHWH uses the weak to defeat his enemies | Marvelling at the way in which YHWH uses that which is weak to accomplish his purposes | ||||

| לְמַ֥עַן צוֹרְרֶ֑יךָ | because of your adversaries, | |||||||||

| לְהַשְׁבִּ֥ית א֝וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם׃ | in order to put an end to a vengeful enemy. | |||||||||

| 4 | כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶ֣ה שָׁ֭מֶיךָ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י אֶצְבְּעֹתֶ֑יךָ | When I see your heavens, that which your fingers made, | Interrogative | Expressive | Expressing an opinion about the apparent insignificance of humans in comparison to creatures in the heavenly realm | Interrogative מה "functions as an introduction to a rhetorical question in which a speaker usually expresses a value judgment about something or someone. This value judgment is usually negative" (BHRG 42.3.6). | ||||

| יָרֵ֥חַ וְ֝כוֹכָבִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה׃ | the moon and stars which you have established, | |||||||||

| 5 | מָֽה־אֱנ֥וֹשׁ כִּֽי־תִזְכְּרֶ֑נּוּ | what is mankind that you should consider them, | ||||||||

| וּבֶן־אָ֝דָ֗ם כִּ֣י תִפְקְדֶֽנּוּ׃ | or a human being, that you should be mindful of him? | |||||||||

| 6 | וַתְּחַסְּרֵ֣הוּ מְּ֭עַט מֵאֱלֹהִ֑ים | And you caused him to lack being a heavenly being by a little, | Declarative | Assertive | Describing how YHWH gave humans a surprisingly high status, not far from heavenly being | |||||

| וְכָב֖וֹד וְהָדָ֣ר תְּעַטְּרֵֽהוּ׃ | and you crowned him with honor and majesty. | Declarative | Assertive | Describing how YHWH crowned humans with honor and majesty | ||||||

| 7 | תַּ֭מְשִׁילֵהוּ בְּמַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָדֶ֑יךָ | You caused him to rule that which your hands made. | Declarative | Assertive | Describing how YHWH gave authority to humans, causing them to rule his creation | |||||

| כֹּ֝ל שַׁ֣תָּה תַֽחַת־רַגְלָֽיו׃ | You placed everything under his feet. | Declarative | Assertive | Describing the expansive dominion that YHWH gave to humans | ||||||

| 8 | צֹנֶ֣ה וַאֲלָפִ֣ים כֻּלָּ֑ם | Sheep and goats and cattle – all of them, | Declarative | Assertive | ||||||

| וְ֝גַ֗ם בַּהֲמ֥וֹת שָׂדָֽי׃ | and even wild animals, | |||||||||

| 9 | צִפּ֣וֹר שָׁ֭מַיִם וּדְגֵ֣י הַיָּ֑ם | birds in the sky and fish in the sea, | ||||||||

| עֹ֝בֵ֗ר אָרְח֥וֹת יַמִּֽים׃ | that which traverses the paths of the sea. | |||||||||

| 10 | יְהוָ֥ה אֲדֹנֵ֑ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֥יר שִׁ֝מְךָ֗ בְּכָל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃ | YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth. | Interrogative | Expressive | Praising YHWH for his majesty. | Praising YHWH for his majesty |

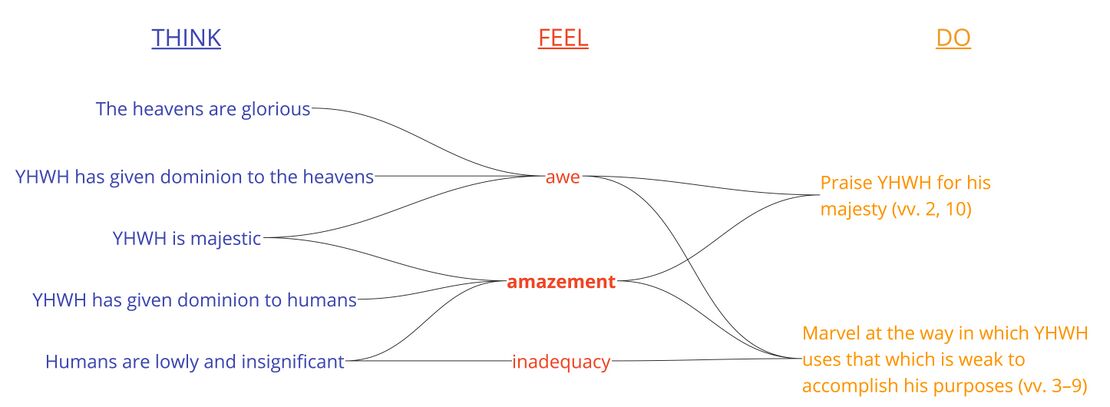

Emotional Analysis

This layer explores the emotional dimension of the biblical text and seeks to uncover the clues within the text itself that are part of the communicative intent of its author. The goal of this analysis is to chart the basic emotional tone and/or progression of the psalm.

For a detailed explanation of our method, see the Emotional Analysis Creator Guidelines.

Emotional Analysis Chart

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| Verse | Text (Hebrew) | Text (CBC) | Proposition (Emotional Analysis) | The Psalmist Feels | Emotional Analysis Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | לַמְנַצֵּ֥חַ עַֽל־הַגִּתִּ֗ית מִזְמ֥וֹר לְדָוִֽד׃ | For the director. On the gittith. A psalm by David. | |||

| 2 | יְהוָ֤ה אֲדֹנֵ֗ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֣יר שִׁ֭מְךָ בְּכָל־הָאָ֑רֶץ | YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth, | YHWH is majestic | • amazed at how majestic YHWH's name is in all the earth | |

| אֲשֶׁ֥ר תְּנָ֥ה ה֝וֹדְךָ֗ עַל־הַשָּׁמָֽיִם׃ | you whose glory is bestowed on the heavens. | YHWH bestows glory on the heavens | |||

| 3 | מִפִּ֤י עֽוֹלְלִ֨ים ׀ וְֽיֹנְקִים֮ יִסַּ֪דְתָּ֫ עֹ֥ז | Out of the mouths of nursing children, you have founded a fortress, | YHWH protects his people from enemies | • amazed that YHWH would use the most vulnerable, nursing children, to put an end to his enemies | |

| לְמַ֥עַן צוֹרְרֶ֑יךָ | because of your adversaries, | ||||

| לְהַשְׁבִּ֥ית א֝וֹיֵ֗ב וּמִתְנַקֵּֽם׃ | in order to put an end to a vengeful enemy. | YHWH puts an end to a vengeful enemy | |||

| 4 | כִּֽי־אֶרְאֶ֣ה שָׁ֭מֶיךָ מַעֲשֵׂ֣י אֶצְבְּעֹתֶ֑יךָ | When I see your heavens, that which your fingers made, | David sees the sky | • awe at the glory of the heavens (note the sustained apposition) • amazed that humans should receive God's attention ('what' indicating a negative judgment about humans), that they should lack being a heavenly being by only a little, and that they should have dominion over 'all', 'even the wild animals.' • inadequate/humbled ('what is mankind...?') |

|

| יָרֵ֥חַ וְ֝כוֹכָבִ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֣ר כּוֹנָֽנְתָּה׃ | the moon and stars which you have established, | YHWH makes the moon and stars | |||

| 5 | מָֽה־אֱנ֥וֹשׁ כִּֽי־תִזְכְּרֶ֑נּוּ | what is mankind that you should consider them, | Mankind does not deserve YHWH's consideration | ||

| וּבֶן־אָ֝דָ֗ם כִּ֣י תִפְקְדֶֽנּוּ׃ | or a human being, that you should be mindful of him? | Human beings do not deserve YHWH's attention | |||

| 6 | וַתְּחַסְּרֵ֣הוּ מְּ֭עַט מֵאֱלֹהִ֑ים | And you caused him to lack being a heavenly being by a little, | YHWH cause humanity to lack being a heavenly being | ||

| וְכָב֖וֹד וְהָדָ֣ר תְּעַטְּרֵֽהוּ׃ | and you crowned him with honor and majesty. | YHWH crowns humanity with glory and majesty | |||

| 7 | תַּ֭מְשִׁילֵהוּ בְּמַעֲשֵׂ֣י יָדֶ֑יךָ | You caused him to rule that which your hands made. | YHWH causes humanity to rule | ||

| כֹּ֝ל שַׁ֣תָּה תַֽחַת־רַגְלָֽיו׃ | You placed everything under his feet. | YHWH places creatures under humanity's feet |

|||

| 8 | צֹנֶ֣ה וַאֲלָפִ֣ים כֻּלָּ֑ם | Sheep and goats and cattle – all of them, | |||

| וְ֝גַ֗ם בַּהֲמ֥וֹת שָׂדָֽי׃ | and even wild animals, | ||||

| 9 | צִפּ֣וֹר שָׁ֭מַיִם וּדְגֵ֣י הַיָּ֑ם | birds in the sky and fish in the sea, | |||

| עֹ֝בֵ֗ר אָרְח֥וֹת יַמִּֽים׃ | that which traverses the paths of the sea. | ||||

| 10 | יְהוָ֥ה אֲדֹנֵ֑ינוּ מָֽה־אַדִּ֥יר שִׁ֝מְךָ֗ בְּכָל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃ | YHWH, our lord, how majestic is your name in all the earth. | YHWH is majestic | • amazed |

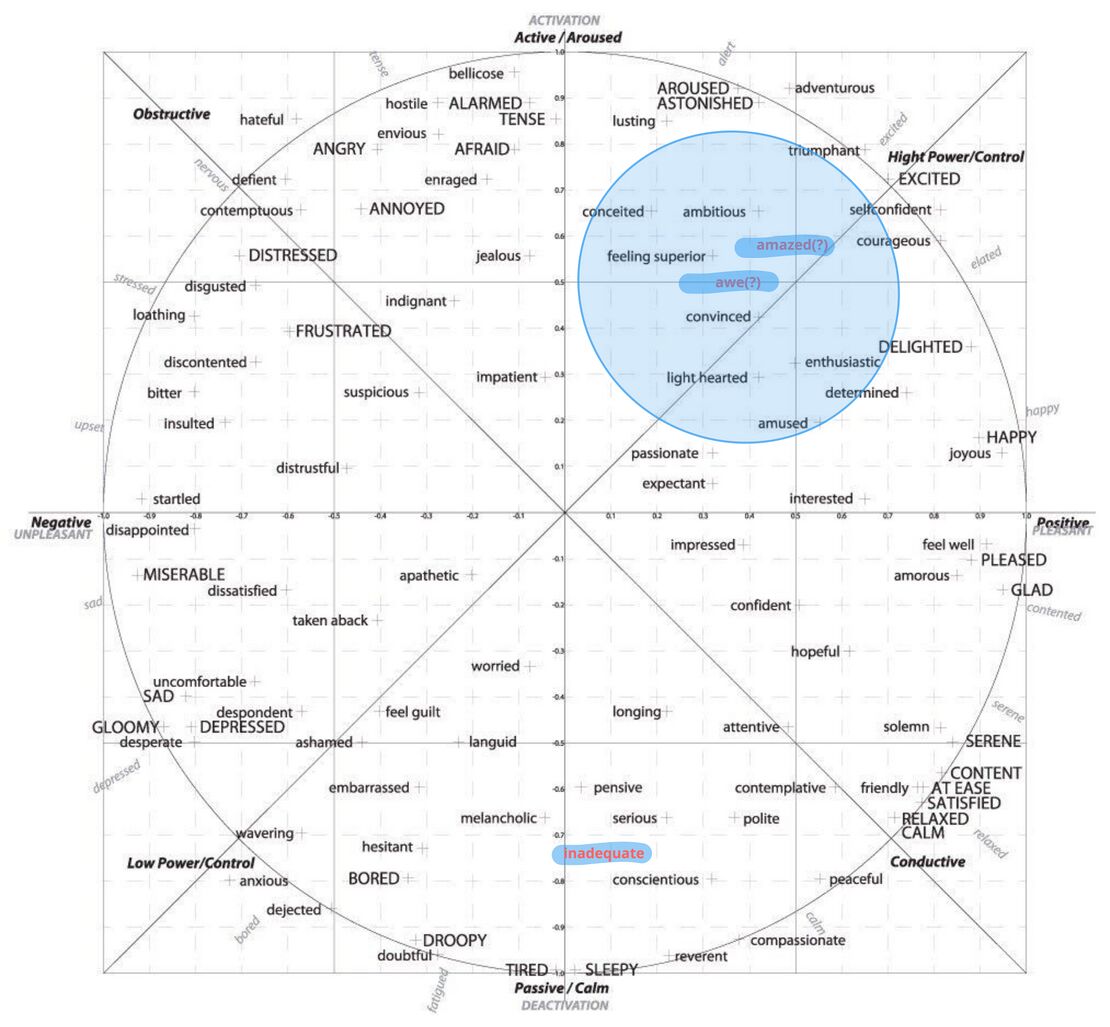

Affective Circumplex

Bibliography

- Alter, Robert. 1985. The Art of Biblical Poetry. New York: Basic Books.

- Anderson, A. A. 1972. The Book of Psalms. Vol. 1. NCBC. Greenwood, SC: Attic.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Barthélemy, Dominique. 2005. Critique Textuelle de l’Ancien Testament. Tome 4: Psaumes. Fribourg, Switzerland: Academic Press.

- Boyd, Stephen W. 2017. “The Binyanim (Verbal Stems).” In Where Shall Wisdom Be Found? A Grammatical Tribute to Professor Stephen A. Kaufman, edited by Hélène M. Dallaire, Benjamin J. Noonan, and Jennifer E. Noonan. Eisenbrauns.

- Bratcher, Robert G., and William D. Reyburn. 1991. A Translator's Handbook on the Book of Psalms. New York: UBS Handbook Series.

- Briggs, Charles and Emilie Briggs. 1906. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Psalms. International Critical Commentary. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons.

- Brown, William. 2002. Seeing the Psalms: A Theology of Metaphor. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- Brueggemann, Walter, and William H. Bellinger Jr. 2014. Psalms. New Cambridge Bible Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Craigie, Peter C. 2004. Word Biblical Commentary: Psalms 1–50. 2nd ed. Vol. 19. Nashville, TN: Nelson Reference & Electronic.

- Dahood, Mitchell J. 1966. The Anchor Bible: Psalms I, 1-50. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1871. Biblical Commentary on the Psalms. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T&T Clark.

- Delitzsch, Franz. 1883. A Commentary on the Psalms. New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

- Eaton, John. 2003. The Psalms: A Historical and Spiritual Commentary with an Introduction and New Translation. London; New York: T&T Clark.

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2003. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 3: The Remaining 65 Psalms). Vol. 3. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Van Gorcum.

- Gentry, Peter J. 1998. “The System of the Finite Verb in Classical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 39:7–39.

- Gentry, Peter J., and Stephen J. Wellum. 2012. Kingdom Through Covenant: A Biblical-Theological Understanding of the Covenants. Wheaton: Crossway.

- Gesenius, W. Donner, H. Rüterswörden, U. Renz, J. Meyer, R. (eds.). 2013. Hebräisches und aramäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament. Berlin: Springer.

- Hengstenberg, Ernst Wilhelm. 1863. Commentary on the Psalms. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Holmstedt, Robert D. 2016. The Relative Clause in Biblical Hebrew. Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 1993. Die Psalmen I: Psalm 1–50. Neue Echter Bibel. Würzburg: Echter.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1855. Die Psalmen. Vol. 1. Gotha: Friedrich Andreas Perthes.

- Ibn Ezra. Ibn Ezra on Psalms.

- Jacobson, R. A. 2014. "Psalm 8," in N. DeClaissé-Walford, R. A. Jacobson & B. L. Tanner (eds.) The Book of Psalms. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

- Jero, Christopher. 2017. “Tense, Mood, and Aspect in the Biblical Hebrew Verbal System.” In Where Shall Wisdom Be Found? A Grammatical Tribute to Professor Stephen A. Kaufman, edited by Hélène M. Dallaire, Benjamin J. Noonan, and Jennifer E. Noonan. Eisenbrauns.

- Keel, Othmar. 1997. The Symbolism of the Biblical World: Ancient Near Eastern Iconography and the Book of Psalms. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Keener, Hubert James. 2013. A Canonical Exegesis of the Eighth Psalm: YHWH’s Maintenance of the Created Order Through Divine Reversal. Vol. 00009. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.

- Kraus, Hans-Joachim. 1988. Psalms 1–59. Minneapolis: Fortress.

- Kraut, Judah. 2010. “The Birds and the Babes: The Structure and Meaning of Psalm 8.” The Jewish Quarterly Review. Vol. 100, No. 1, 10-24.

- Lunn, Nicholas P. 2006. Word-Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: Differentiating Pragmatics and Poetics. Paternoster Biblical Monographs. Milton Keynes: Paternoster.

- Perowne, J. J. Stewart. 1870. The Book of Psalms: A New Translation with Introductions and Notes, Explanatory and Critical. Vol. I. London: Bell and Daldy.

- Robar, Elizabeth. 2013. “Wayyiqol as an Unlikely Preterite.” Journal of Semitic Studies 58 (1): 21–42.

- ________. 2015. The Verb and the Paragraph in Biblical Hebrew: A Cognitive-Linguistic Approach. Vol. 78. Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill.

- Rogerson, J. W., and J. W. McKay. 1977. Psalms. Vol. 1. The Cambridge Bible Commentary on the New English Bible. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ross, Allen P. 2011. A Commentary on the Psalms 1-41. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel.

- Sarna, Nahum M. 1993. On the Book of Psalms: Exploring the Prayers of Ancient Israel. New York: Schocken.

- Smith, Mark S. 1997. "Psalm 8:2b-3: New Proposals for Old Problems." The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. Vol. 59, No. 4, 637-641.

- Sommer, Benjamin. 2020. “Hebrew Humanism. A Commentary on Psalm 8.” 11: 7*-32*. Studies in Bible and Exegesis (עיוני מקרא ופרשנות).

- Stec, David M. 2004. The Targum of Psalms: Translated, with a Critical Introduction, Apparatus, and Notes. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press.

- Tate, Marvin E. 2001. "An Exposition of Psalm 8." Perspectives in Religious Studies. 28 (4), 343-359.

- Terrien, Samuel L. 2003. The Psalms: Strophic Structure and Theological Commentary. ECC. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans.

- VanGemeren, Willem. 2008. Psalms: The Expositor's Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Waltke, Bruce K., J. M. Houston, and Erika Moore. 2010. The Psalms as Christian Worship: A Historical Commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co.

- Whitekettle, Richard. 2006. “Taming the Shrew, Shrike, and Shrimp: The Form and Function of Zoological Classification in Psalm 8.” JBL 125: pp. 749-65.

- Wilson, Gerald H. 2002. The NIV Application Commentary: Psalms. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Young, Dwight W. 1960. “Notes on the Root Ntn in Biblical Hebrew.” Vetus Testamentum 10, no. 4: 457–59.

Footnotes

- ↑ Jacobson 2014, 123.

- ↑ Rogerson and McKay 1977, 42.

- ↑ Jacobson 2014, 123.

- ↑ E.g., Baethgen 1904, 21.

- ↑ Wilson 2002, 203; cf. Ps 2:3; 1 Sam 30:26.

- ↑ Jacobson 2014, 125; cf. Whitekettle 2006, 757-761.

- ↑ Cf. Brown 2002, 137-144.

- ↑ When the entire utterance is new/unexpected, it is a thetic sentence (often called "sentence focus"). See our Creator Guidelines for more information on topic and focus.

- ↑ Frame setters are any orientational constituent – typically, but not limited to, spatio-temporal adverbials – function to "limit the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain" and "indicate the general type of information that can be given" in the clause nucleus (Krifka & Musan 2012: 31-32). In previous scholarship, they have been referred to as contextualizing constituents (see, e.g., Buth (1994), “Contextualizing Constituents as Topic, Non-Sequential Background and Dramatic Pause: Hebrew and Aramaic evidence,” in E. Engberg-Pedersen, L. Falster Jakobsen and L. Schack Rasmussen (eds.) Function and expression in Functional Grammar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 215-231; Buth (2023), “Functional Grammar and the Pragmatics of Information Structure for Biblical Languages,” in W. A. Ross & E. Robar (eds.) Linguistic Theory and the Biblical Text. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 67-116), but this has been conflated with the function of topic. In brief: sentence topics, belonging to the clause nucleus, are the entity or event about which the clause provides a new predication; frame setters do not belong in the clause nucleus and rather provide a contextual orientation by which to understand the following clause.

- ↑ BHRG 46.2.3.1.

- ↑ Cf. Ps 36:8.

- ↑ BHRG 42.3.6, citing Ps 8:2/10 as an example.

- ↑ So Lunn 2006, 296 – "MKD".

- ↑ Cf. GKC 159dd; IBHS 38.7a.

- ↑ IBHS 38.3b.