Psalm 121 Poetry

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: Poetic Structure and Poetic Features.

Poetic Structure

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Macro-structure

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

| SS | Song of Ascents | |||

| v. 1 Song of the Ascents I lift my eyes toward the mountains. Where will my help come from? | My help | My help comes from YHWH, the one who made heaven and earth. |

confidence | |

| v. 2 My help is from YHWH, the one who made heaven and earth. | ||||

| v. 3 May he not let your foot slip! May the one who guards you not doze off! | Your guard | YHWH will guard you from all harm – day and night, as you come and go from now until forever. |

confidence | |

| v. 4 Indeed, the one who guards Israel will not doze off and will not fall asleep. | ||||

| v. 5 YHWH is the one who guards you. YHWH is your shade over your right hand. | ||||

| v. 6 During the day, the sun will not strike you, nor the moon at night. | ||||

| v. 7 YHWH will guard you from all harm. He will guard your life. | ||||

| v. 8 YHWH will guard your going out and your coming in from now until forever. | ||||

Notes

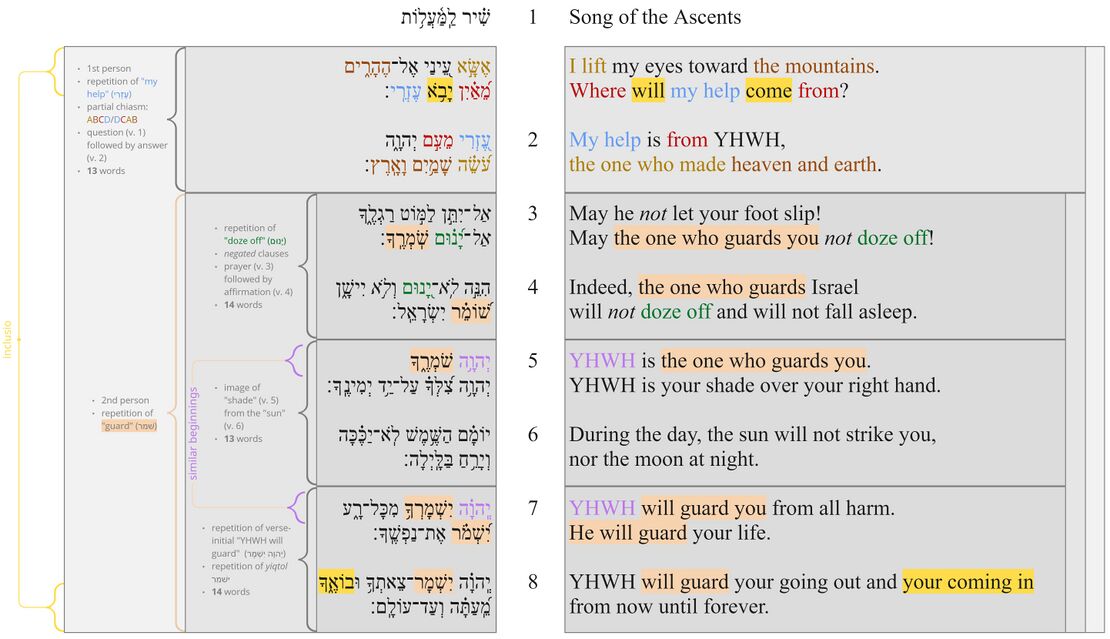

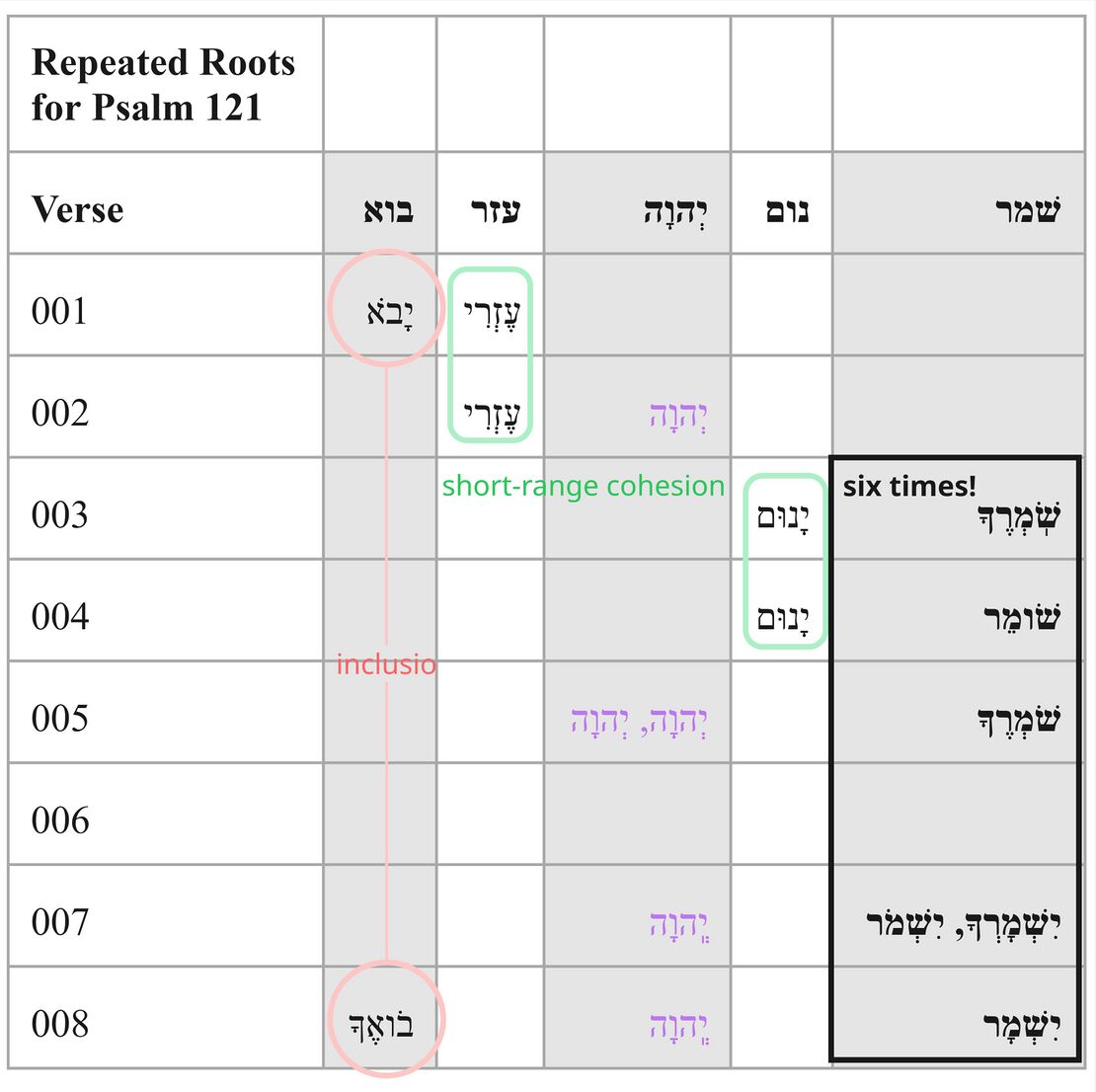

- The poem is bound by an inclusio (בוא, vv. 1, 8) and united by the common theme of YHWH's protection, exemplified by the key word "guard" (שׁמר), which appears six (!) times (vv. 3–8). Although the word "guard" does not appear in vv. 1–2, it is closely related to the idea of "help" – both words involve protection from danger – and to the image of "lifting one's eyes" – the basic meaning of שׁמר is to "watch" (see lexical semantics).

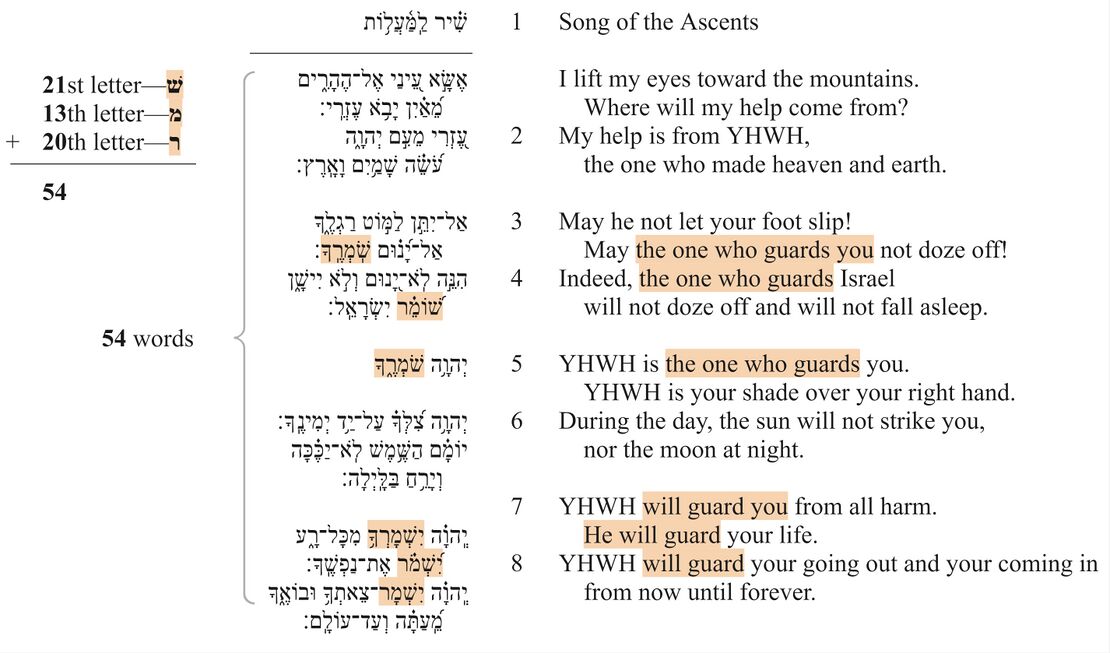

- There are 54 words in the poem, corresponding to the numerical value of the key-word "guard" (שׁמר).[1] (Note that this word count disregards the maqqefs in the Masoretic Text and counts each individual grapheme as its own word.)

- Shin = 21 (21st letter of the alphabet);

- Mem =13 (13th letter of the alphabet);

- Resh = 20 (20th letter of the alphabet)

- The psalm divides into two main parts: vv. 1–2 and vv. 3–8.[2] Two features support this structure:

- The key-word word שׁמר only occurs in vv. 3–8, not in vv. 1–2.

- There is a shift in person between vv. 1–2 (first person) and vv. 3–8 (second person). For the significance of this shift, see The Voice(s) in Psalm 121.

- Others argue plausibly that the psalm divides into two halves (vv. 1–4; vv. 5–8), with each half consisting of eight lines and 27 words.[3] Under this schema, the first half is bound by a similar pattern of question/prayer (irrealis) (vv. 1, 3) followed by confident affirmation (realis) (vv. 2, 4).[4] Another feature that binds this first half according to this schema is the use of link-words to unite the sub-sections: עֶזְרִי in vv. 1b–2a and יָנוּם in vv. 3b–4a. The second half according to this schema is bound by the repetition of "YHWH is the one who guards you" // "YHWH will guard you" at the beginning of vv. 5, 7.

- The second main part (vv. 3–8) subdivides into three parts, thus creating four sub-sections throughout the psalm (vv. 1–2, vv. 3–4, vv. 5–6, vv. 7–8).[5] Each sub-section is about the same length (4 lines and 13 words / 4 lines and 14 words / 4 lines and 13 words / 4 lines and 14 words).

- The first sub-section (vv. 1–2) is bound by the repetition of "my help" (עֶזְרִי), which is actually part of a larger chiasm in these verses: A. "I lift" (אשא); B. "the mountains"; C. "from where"; D. "my help" // D. "my help"; C. "from YHWH"; A. "maker" (עשה , sounds similar to אשא); B. "heaven and earth" (related to "mountains" – all are cosmological terms; also mountains stand in between heaven and earth).

- The second sub-section (vv. 3–4) is bound by the repetition of the rare word "doze off" (יָנוּם). The use of negators ("not...not...not...not") also binds these verses together.

- The third sub-section (vv. 5–6) is bound by its imagery: the "shade" mentioned in v. 5 gives protection from the "sun" mentioned in v. 6.

- The fourth sub-section (vv. 7–8) is bound by the especially dense repetition of ישׁמר (yiqtol), which occurs in every clause. The two verses in this section also have the same beginning: יְהוָה יִשְׁמָרְ.

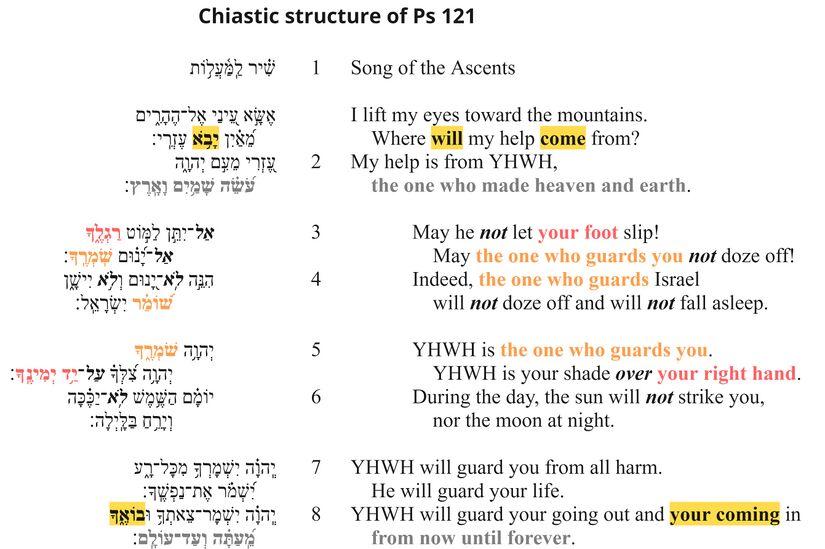

- These four sub-sections are also arranged as a chiasm, uniting the whole poem.[6]

- The first sub-section (vv. 1–2) corresponds to the last sub-section (vv. 7–8) through the repetition of the word "come" (בוא) as well as the similarities between final lines of these section: "the one who made heaven and earth" and "from now until forever." Both of these phrases are merisms. Also, both phrases are instances of enjambment that conclude a sub-section.

- The middle sections (vv. 3–4 and vv. 5–6) correspond to one another by the repetition of the participle שׁומר (vv. 3b, 4b, 5a), the use of negators (vv. 3–4, 6; note also עַל in v. 5, which sounds similar, though not identical to, the negator אַל), and the mention of body parts (v. 3: "your foot"; v. 5: "your right hand").

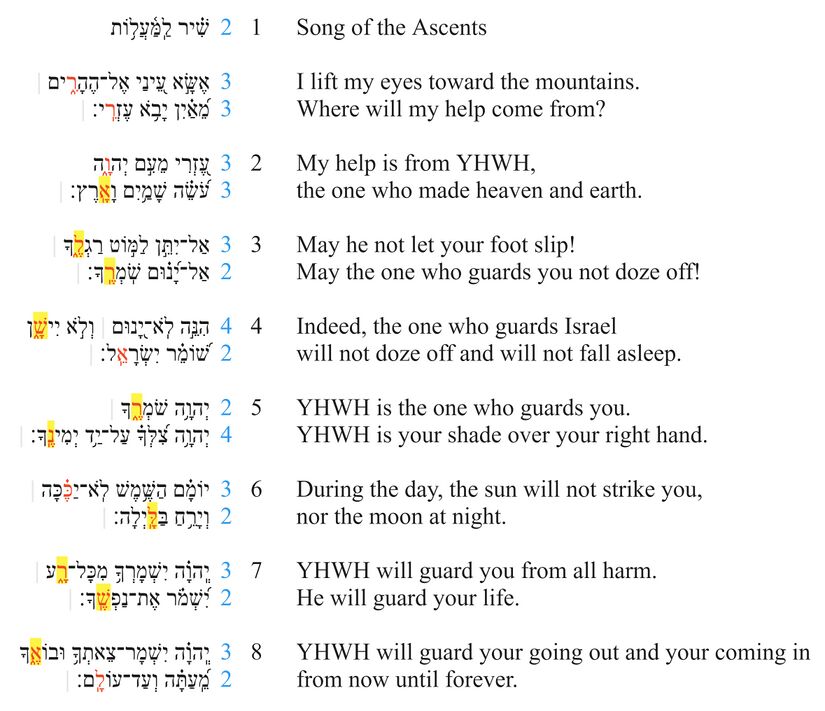

Line Divisions

Line division divides the poem into lines and line groupings. We determine line divisions based on a combination of external evidence (Masoretic accents, pausal forms, manuscripts) and internal evidence (syntax, prosodic word counting and patterned relation to other lines). Moreover, we indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing.

When line divisions are uncertain, we consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. Then, if a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences our decision to divide the text at a certain point, we place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

| Poetic line division legend | |

|---|---|

| Pausal form | Pausal forms are highlighted in yellow. |

| Accent which typically corresponds to line division | Accents which typically correspond to line divisions are indicated by red text. |

| | | Clause boundaries are indicated by a light gray vertical line in between clauses. |

| G | Line divisions that follow Greek manuscripts are indicated by a bold green G. |

| DSS | Line divisions that follow the Dead Sea Scrolls are indicated by a bold green DSS. |

| M | Line divisions that follow Masoretic manuscripts are indicated by a bold green M. |

| Number of prosodic words | The number of prosodic words are indicated in blue text. |

| Prosodic words greater than 5 | The number of prosodic words if greater than 5 is indicated by bold blue text. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

- The division of this psalm into lines is relatively straightforward. The division above agrees with the Masoretic accents,[7] the pausal forms, and the Septuagint (according to Rahlfs 1931).

- There is enjambment in vv. 2, 4, 8, each time at the end of a poetic unit (see Poetic Structure).

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

The One Who Guards

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

The word "guard" (שׁמר) occurs six times in this short eight-verse psalm (vv. 3, 4, 5, 7, 8).

The psalm has 54 words.[8] (Note that this word count excludes the superscription and disregards the maqqefs in the Masoretic Text and counts each individual grapheme as its own word.) The number 54 corresponds to the numerical value of the word שׁמר, if each letter in the word is assigned a value according to its position in the Hebrew alphabet.

Shin (שׁ) is the 21st letter of the alphabet Mem (מ) is the 13th letter of the alphabet Resh (ר) is the 20th letter of the alphabet.

21 + 13 + 20 = 54.

(Note that shin [שׁ] and sin [שׂ] are not counted as separate letters in the biblical acrostic poems.)

Effect

The word שׁמר is, by far, the most prominent word in this poem. Not only is it repeated six times within such a short span of text, but the numerical value of this word has determined the exact length of the poem. It is clear that the poet wants his readers to remember this idea above all: YHWH guards his people.

Anywhere, Anytime

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

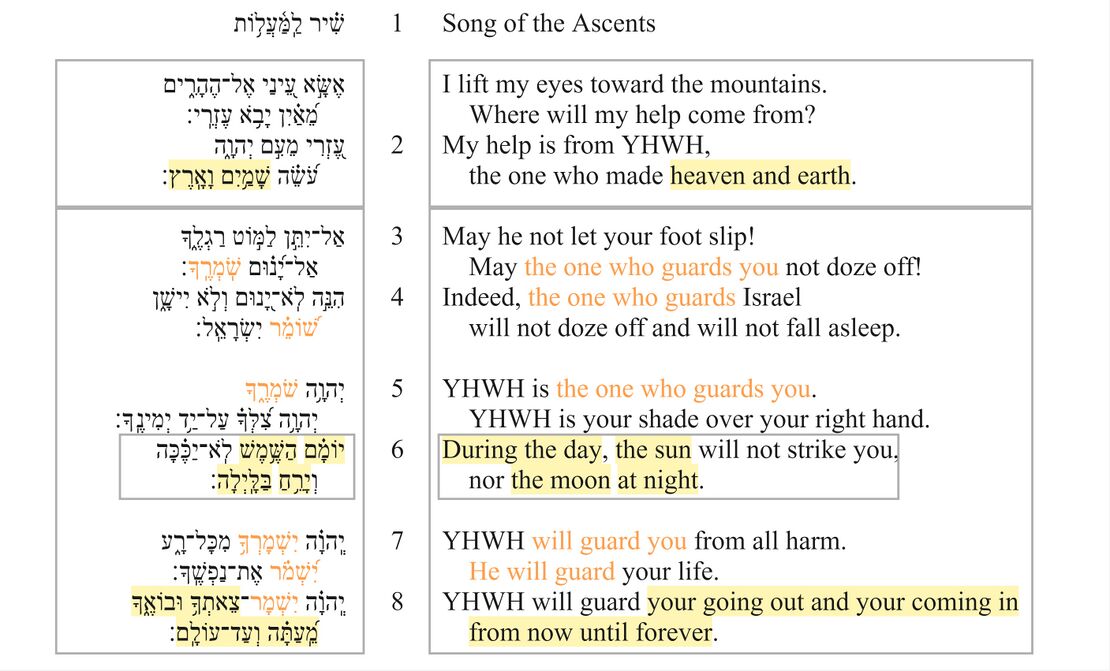

Psalm 121 contains several merisms.[9]

1. "heaven and earth" (v. 2) 2. "during the day... at night" (v. 6) 3. "sun... moon" (v. 6) 4. "your going out and your coming in" (v. 8a) 5. "from now until forever" (v. 8b)

Furthermore, these merisms occur at key structural points in the text. The first merism concludes the first main part of the psalm (v. 2, see poetic Structure), and the last two merisms conclude the psalm as a whole (v. 8). The second and third merisms both occur in v. 6, which stands out as a central verse in the main body of the psalm (vv. 3–8) – it is the only verse in this section that does not have the word "guard" (שׁמר), with this word occurring three times before this verse and three times after it. Verse 6 is also structured as an elaborate chiasm: a. "during the day" b. "sun" c. "will not strike you" b. "moon" a. "at night"

Effect

The use of merisms at strategic points in the text highlights the all-encompassing nature of YHWH's protection.

As the one who made the whole universe (v. 2: "heaven and earth"), YHWH is able to guard his people from every heavenly power (v. 6: "sun... moon") at every moment of the day (v. 6: "during the day... at night") in all that they do (v. 8a: "your going out and your coming in") for all of time (v. 8b: "from now until forever").

YHWH Guards Israel

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

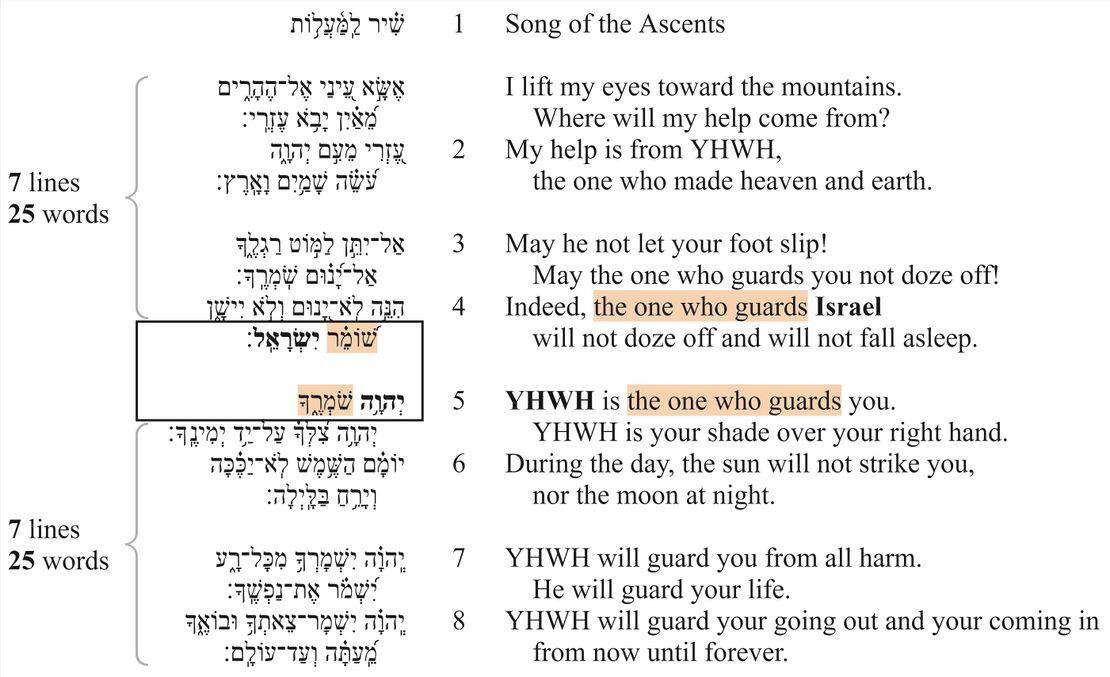

The numeric center of the psalm is vv. 4b–5a. These two lines are flanked on either side by seven lines and 25 words.

These two lines are exceptionally short – the two shortest lines in the psalm in terms of word and syllable count (2 words, 5–6 syllables). (The only other two-word line is v. 6b. In terms of syllables, this line is slightly longer than the lines in vv. 4b–5a.)

These two lines form a chiasm:

a. "one who guards" b. "Israel" (proper name) b. "YHWH" (proper name) a. "one who guards"

(Note also the theophoric element in the name "Israel" [אל = "God"], which further strengthens the chiastic connection between "Israel" and "YHWH").

Effect

The centrality of vv. 4b–5a brings into sharp focus the psalm's main theme ("guarding") and its two main participants ("Israel" and "YHWH"). The whole message of the psalm can be summarized with these few words: "YHWH guards Israel."

Repeated Roots

The repeated roots table is intended to identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm.

| Repeated Roots legend | |

|---|---|

| Divine name | The divine name is indicated by bold purple text. |

| Roots bounding a section | Roots bounding a section, appearing in the first and last verse of a section, are indicated by bold red text. |

| Roots occurring primarily in the first section are indicated in a yellow box. | |

| Roots occurring primarily in the third section are indicated in a blue box. | |

| Roots connected across sections are indicated by a vertical gray line connecting the roots. | |

| Section boundaries are indicated by a horizontal black line across the chart. | |

Bibliography

- Assmann, Jan. Ägyptische Hymnen und Gebete. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Freiburg/Göttingen: Universitäts Verlag/Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1904.

- Berlin, Adele, Avigdor Shinan, and Benjamin D. Sommer. The JPS Bible Commentary: Psalms 120–150: תהלים קכ–קנ. University of Nebraska Press, 2023.

- Bojowlad, Stefan. “Eine Ägyptische Parallele Für Ps 121,3-4.” Biblische Notizen 191 (2021): 59–63.

- Bullinger, E.W. Figures of Speech Used in the Bible. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1968.

- Chrysostom, John. St. John Chrysostom Commentary on the Psalms. Translated by Robert C. Hill. Brookline, Mass: Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 1998.

- Creach, Jerome. “Psalm 121.” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology 50, no. 1 (1996): 47–51.

- Emmendörffer, Michael. “Psalm 121 – Jahwe als Wächter des Lebens. Ein Dokument später Psalmenfrömmigkeit.” In Über Psalmen: Interdisziplinäre Studien zum Psalter und seiner Rezeption, edited by Michael Pietsch and Christian Rose, 11–22. Theologische Akzente 11. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2025.

- Fokkelman, J.P. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 2: 85 Psalms and Job 4–14). Vol. 2. Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Van Gorcum, 2000.

- Gentry, Peter J. 1998. “The System of the Finite Verb in Classical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 39: 7–39.

- Gentry, Peter J., and Stephen J. Wellum. Kingdom Through Covenant: A Biblical-Theological Understanding of the Covenants. Wheaton: Crossway, 2012.

- Goldingay, John. Psalms: Psalms 90-150. Vol. 3. BCOT. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008.

- Kennicott, Benjamin. Vetus testamentum hebraicum : cum variis lectionibus, 1776.

- Longacre, Drew. “The 11Q5 Psalter as a Scribal Product: Standing at the Nexus of Textual Development, Editorial Processes, and Manuscript Production.” ZAW 134, no. 1 (2022): 85–111.

- Longman III, Tremper. “Merism.” Dictionary of the Old Testament Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. Edited by Tremper Longman III and Peter Enns. Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2008.

- Lunn, Nicholas P. Word-Order Variation in Biblical Hebrew Poetry: Differentiating Pragmatics and Poetics. Paternoster Biblical Monographs. Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2006.

- van der Lugt, Pieter. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. Vol. 3. Oudtestamentische Studiën 63. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Maré, Leonard P. “Psalm 121: Yahweh’s Protection against Mythological Powers.” Old Testament Essays (New Series) 19, no. 2 (2006): 712–722.

- Miller-Naudé, Cynthia L., and C.H.J. van der Merwe. “הִנֵּה and Mirativity in Biblical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 52 (2011): 53–81.

- Notarius, Tania. The Verb in Archaic Biblical Poetry: A Discursive, Typological, and Historical Investigation of the Tense System. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- de Regt, Lénart J. Linguistic Coherence in Biblical Hebrew Texts. Revised and Extended edition. Perspectives on Hebrew Scriptures and its Contexts 28. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2019.

- Rendsburg, Gary. How the Bible Is Written. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2019.

- Robar, Elizabeth. “Morphology and Markedness: On Verb Switching in Hebrew Poetry.” Journal for Semitics 30, no. 2 (2021): 1–17.

- Sanders, James A. The Psalms Scroll of Qumrân Cave 11 (11QPsa). DJD 4. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965.

- Schmitt, Armin. “Zum literarischen und theologischen Profil von Ps 121.” Biblische Notizen 97 (1999): 55–84.

- Sjörs, Ambjörn. Historical Aspects of Standard Negation in Semitic. Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics 91. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2018.

- Staszak, Martin. The Preposition Min. Beiträge zur Wissenschaft vom Alten und Neuen Testament (BWANT) 246. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2024.

- Stol, Marten. Epilepsy in Babylonia. Cuneiform Monographs 2. Groningen: Styx Publications, 1993.

- Taylor, Richard A. The Syriac Peshitta Bible with English Translation. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2020.

- Theodoret. Commentary on the Psalms. Translated by Robert C. Hill. The Fathers of the Church 101-102. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2001.

- Weber, Beat. Werkbuch Psalmen II: Die Psalmen 73 Bis 150. 2., Aktualisierte Auflage. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer, 2016.

- Willis, John T. “Psalm 121 As a Wisdom Poem.” Hebrew Annual Review 11 (1987): 435–51.

- Witthoff, David J. "The Relationships of the Senses of נֶפֶשׁ in the Hebrew Bible: A Cognitive Linguistics Perspective." PhD Dissertation, University of Stellenbosch, 2021.

- Zenger, Erich. “Psalm 121.” In Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150, by Frank Lothar Hossfeld and Erich Zenger, 315–331. Hermeneia. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2011.

Footnotes

- ↑ cf. Labuschagne, cited in van der Lugt 2013, 352.

- ↑ See e.g., Emmendörffer 2025; Fokkelman 2000, 271; cf. Auffret 1999, 13–23; Maré 2006.

- ↑ E.g., van der Lugt 2013, 350.

- ↑ See Creach 1996, 49–50; cf. van der Lugt 2013, 354.

- ↑ Cf. Weber 2016, 278–280; Zenger 2011, 319–320.

- ↑ cf. Weber 2016, 279–280.

- ↑ Cf. de Hoop and Sanders 2022.

- ↑ Cf. Labuschagne, cited in van der Lugt 2013, 352.

- ↑ Cf. Auffret 1999, 13–23; Fokkelman 2000, 271–273. "Merism is a literary device that uses an abbreviated list to suggest the whole. The most common type of merism cites the poles of a list to suggest everything in between" (Longman 2008, 464).