Psalm 111 Poetry

Guardian: Ryan Sikes

About the Poetics Layer

Exploring the Psalms as poetry is crucial for understanding and experiencing the psalms and thus for faithfully translating them into another language. This layer is comprised of two main parts: Poetic Structure and Poetic Features.

Poetic Structure

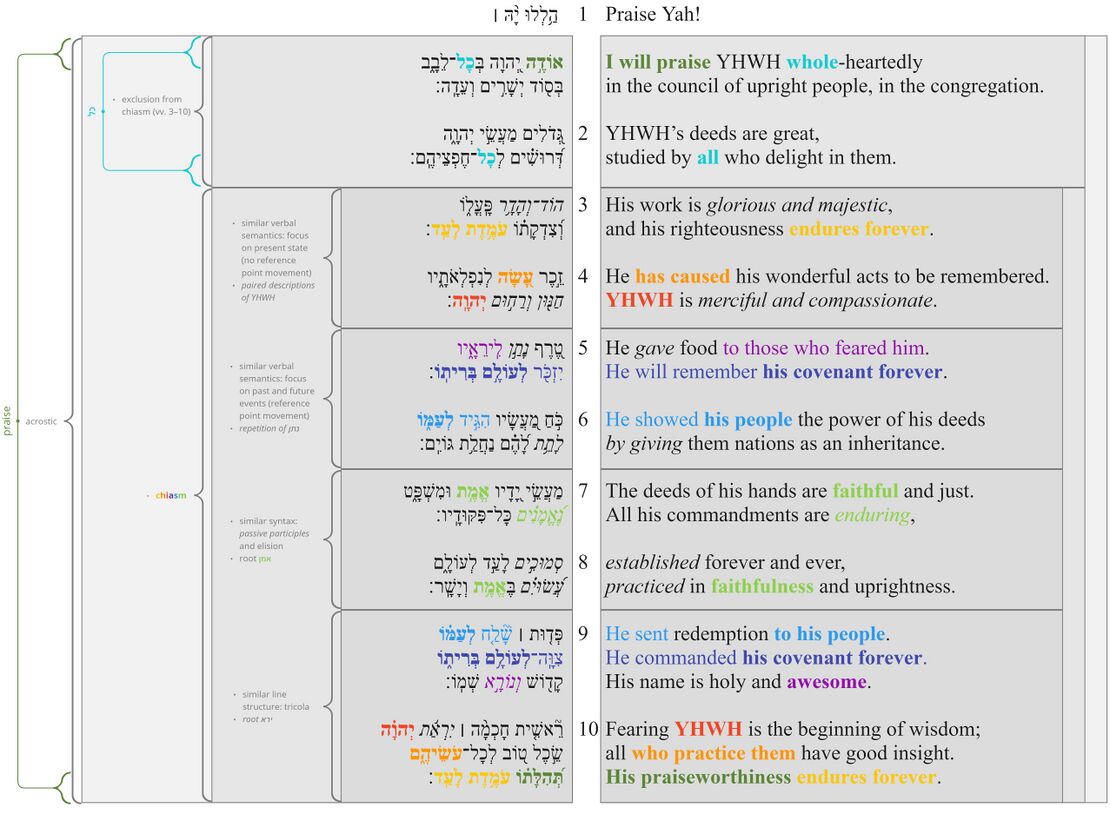

In poetic structure, we analyse the structure of the psalm beginning at the most basic level of the structure: the line (also known as the “colon” or “hemistich”). Then, based on the perception of patterned similarities (and on the assumption that the whole psalm is structured hierarchically), we argue for the grouping of lines into verses, verses into sub-sections, sub-sections into larger sections, etc. Because patterned similarities might be of various kinds (syntactic, semantic, pragmatic, sonic) the analysis of poetic structure draws on all of the previous layers (especially the Discourse layer).

Poetic Macro-structure

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

- vv. 3–10. The major division in the psalm is between vv. 1–2 and vv. 3–10. This division is based primarily on the chiasm that spans vv. 3b–10c (see poetic feature #2). Although it is not part of the chiasm, v. 3a is joined to the unit of vv. 3b–10a by means of both syntax (conjunctive waw in v. 3b) and prosody (v. 3 is a single prosodic unit, a Masoretic verse). The unit consisting of vv. 3–10 is subdivided into four smaller units of two verses each (cf. van der Lugt 2014:235).

- vv. 3–4. The first subunit is united by similar verbal semantics. Each clause in this unit shows a lack of reference point movement: "is... stands... has caused... is." In each clause (even the one clause that uses a qatal verb), the focus is on the present/resultant state. The unit is further united by the repetition—at the beginning and end of the unit—of pairs of words praising YHWH: הוֹד־וְהָדָ֥ר (v. 3a) and חַנּ֖וּן וְרַח֣וּם (v. 4b) (cf. van der Lugt 2014:236).

- vv. 5–6. In vv. 5–6, all of the main verbs have reference point movement: "he gave... he will remember... he showed..." Whereas the focus of the previous unit was on present states, the focus of this unit is on YHWH's past actions (vv. 5a, 6ab) and their future implications (v. 5b). The verb נתן also occurs in the first and last line of this unit (cf. Auffret 1997; van der Lugt 2014:236).

- vv. 7–8. The third subunit may be the most clearly defined. This unit is formed by the repetition of the root אמן, the repetition of passive participles (vv. 7b, 8a, 8b) and the fact that כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו is the subject in three out of the four lines (vv. 7b, 8a, 8b). Furthermore, the unit is framed, like vv. 3–4, by pairs of words joined by waw: אֱמֶ֣ת וּמִשְׁפָּ֑ט (v. 7a) and בֶּאֱמֶ֥ת וְיָשָֽׁר (v. 8b).

- vv. 9–10. The fourth sub-unit is united by the fact that these two verses are the only two tricola in the psalm. They are further stitched together by the repetition of the root ירא at the end of v. 9 and the beginning of v. 10.

- vv. 1–2. The first two verses of the psalm form a unit. They are united not only by their exclusion from the chiasm (vv. 3–10), but also by the repetition of כל at the beginning and end of the unit (vv. 1a, 2b). Together, these two verses serve as a kind of introduction to the psalm. In v. 1, the psalmist states his intention to "praise YHWH", and in v. 2 he states the main theme of his praise: "YHWH's deeds" (v. 2a) and the human response to them (v. 2b) (cf. Scoralick 1997:198).

- The whole psalm is framed by an inclusio (words belonging to the semantic domain of praise: אודה and תהלתו). The word תהלתו in v. 10c also corresponds to the superscription הַ֥לְלוּ יָ֨הּ ׀.

- The structural analysis above agrees with van der Lugt (2014) in terms of the division of smaller units (vv. 1–2; vv. 3–4; vv. 5–6; vv. 7–8; vv. 9–10) but with Scoralick (1997) in terms of the division of larger units (vv. 1–2; vv. 3–10). For other structural analyses, see Auffret 1997, Weber 2003, Fokkelman 2003, Kiel 2022.

Line Divisions

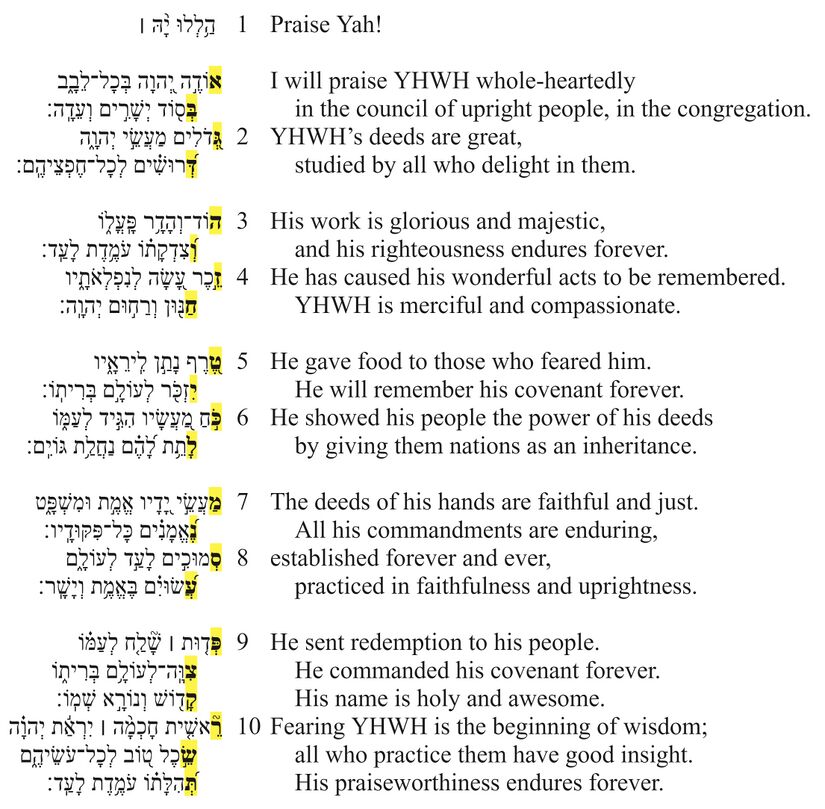

Line division divides the poem into lines and line groupings. We determine line divisions based on a combination of external evidence (Masoretic accents, pausal forms, manuscripts) and internal evidence (syntax, prosodic word counting and patterned relation to other lines). Moreover, we indicate line-groupings by using additional spacing.

When line divisions are uncertain, we consult some of the many psalms manuscripts which lay out the text in lines. Then, if a division attested in one of these manuscripts/versions influences our decision to divide the text at a certain point, we place a green symbol (G, DSS, or MT) to the left of the line in question.

| Poetic line division legend | |

|---|---|

| Pausal form | Pausal forms are highlighted in yellow. |

| Accent which typically corresponds to line division | Accents which typically correspond to line divisions are indicated by red text. |

| | | Clause boundaries are indicated by a light gray vertical line in between clauses. |

| G | Line divisions that follow Greek manuscripts are indicated by a bold green G. |

| DSS | Line divisions that follow the Dead Sea Scrolls are indicated by a bold green DSS. |

| M | Line divisions that follow Masoretic manuscripts are indicated by a bold green M. |

| Number of prosodic words | The number of prosodic words are indicated in blue text. |

| Prosodic words greater than 5 | The number of prosodic words if greater than 5 is indicated by bold blue text. |

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Notes

- Given the acrostic structure, whereby each line begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet, each line is clearly marked.

Poetic Features

In poetic features, we identify and describe the “Top 3 Poetic Features” for each Psalm. Poetic features might include intricate patterns (e.g., chiasms), long range correspondences across the psalm, evocative uses of imagery, sound-plays, allusions to other parts of the Bible, and various other features or combinations of features. For each poetic feature, we describe both the formal aspects of the feature and the poetic effect of the feature. We assume that there is no one-to-one correspondence between a feature’s formal aspects and its effect, and that similar forms might have very different effects depending on their contexts. The effect of a poetic feature is best determined (subjectively) by a thoughtful examination of the feature against the background of the psalm’s overall message and purpose.

YHWH's Deeds from A to Z

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

Psalm 111 is an acrostic poem, in which each line begins with a successive letter of the Hebrew alphabet (cf. Ps. 112).

Effect

The alphabet is a symbol of completeness.[1] In an acrostic poem, the poet takes a topic (e.g., Torah [Ps. 119], or the virtuous woman [Prov. 31]) and expounds on it completely (from every possible angle), so that the reader walks away with a high-resolution image of the topic (i.e., he/she understands it “from A to Z”). In Psalm 111, the topic is "YHWH's deeds" (מַעֲשֵׂי יְהוָה).

Eternal Commands

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

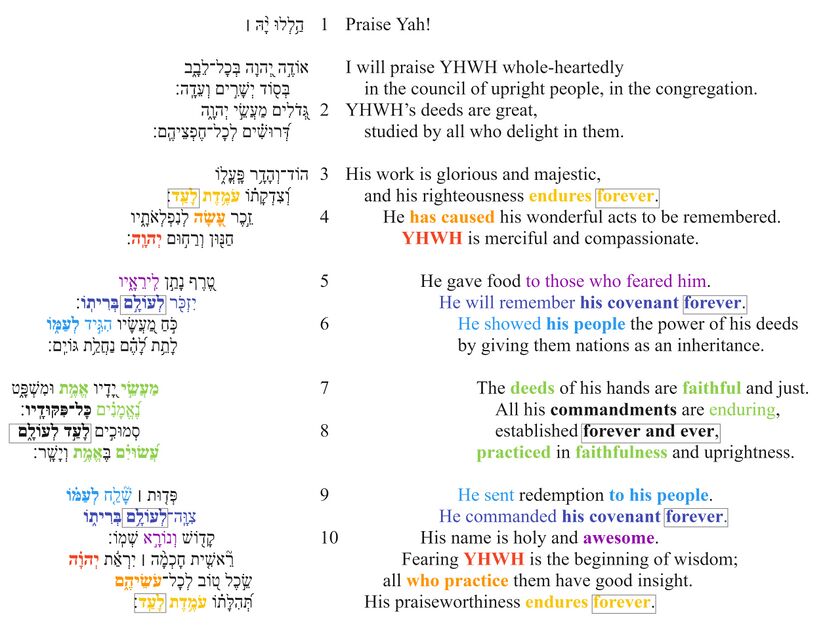

The repetition of roots, words, and phrases forms a chiasm that spans vv. 3b–10c.[2]

a. עֹמֶדֶת לָעַֽד (v. 3b)

b. עָשָׂה (v. 4a)

c. יְהוָֽה (v. 4b)

d. לִֽירֵאָיו (v. 5a)

e. לְעוֹלָם בְּרִיתוֹ (v. 5b)

f. לְעַמּוֹ (v. 6a)

g. מַעֲשֵׂי...אֱמֶת (v. 7a)

X. נֶאֱמָנִים כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו סְמוּכִים לָעַד לְעוֹלָם (v. 7b–8a)

g.' עֲשׂוּיִם בֶּאֱמֶת (v. 8b)

f.' לְעַמּוֹ (v. 9a)

e.' לְעוֹלָם בְּרִיתוֹ (v. 9b)

d.' וְנוֹרָא (v. 9c)

c.' יְהוָה (v. 10a)

b.' עֹשֵׂיהֶם (v. 10b)

a.' עֹמֶדֶת לָעַֽד (v. 10c)

At the center of the chiasm is the three-fold repetition of the root אמן, the phrase כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו, and the phrase לָעַד לְעוֹלָם (cf. the concentric references to time: a/a': לָעַד; e/e': לְעוֹלָם; X: לָעַד לְעוֹלָם). The centrality of כָּל־פִּקּוּדָֽיו is reinforced by the fact that this phrase is the subject of three consecutive clauses (vv. 7b, 8ab) and is still active in the discourse in v. 10, such that it is available for pronominal reference (עֹשֵׂיהֶם in v. 10b).

Effect

Psalm 111 is a celebration of YHWH's deeds. These deeds include redeeming his people from Egypt (v. 9a), sustaining them in the wilderness (v. 5a) and giving them the promised land (v. 6). Although the psalm celebrates all of these deeds (and more), the chiastic structure highlights one deed in particular: YHWH's commands (v. 7b). By placing the "commands" at the center of the chiasm, describing them with the phrase "forever and ever", and making them the subject of three consecutive verses (vv. 7b–8b), the "commands" receive special prominence. Furthermore, the "commands" are surrounded by the threefold repetition of the root אמן. YHWH's commands are both given (by him) in faithfulness and they are to be done (by his people) in faithfulness. This movement at the center of the chiasm (vv. 7–8) from YHWH's faithfulness to his people's faithfulness is part of a larger movement within the chiasm as a whole: the first half of the chiasm (vv. 3–7) focuses on YHWH's character and deeds and the second half (vv. 8b–10) focuses more on the implications for YHWH's people (who, having been redeemed by him, keep his covenant, fear him, and praise him). The pivotal point of this movement from YHWH's deeds to the deeds of his people are YHWH's eternal commands (v. 7b-8a).

Great Deeds

If an emendation or revocalization is preferred, that emendation or revocalization will be marked in the Hebrew text of all the visuals.

| Emendations/Revocalizations legend | |

|---|---|

| *Emended text* | Emended text, text in which the consonants differ from the consonants of the Masoretic text, is indicated by blue asterisks on either side of the emendation. |

| *Revocalized text* | Revocalized text, text in which only the vowels differ from the vowels of the Masoretic text, is indicated by purple asterisks on either side of the revocalization. |

Feature

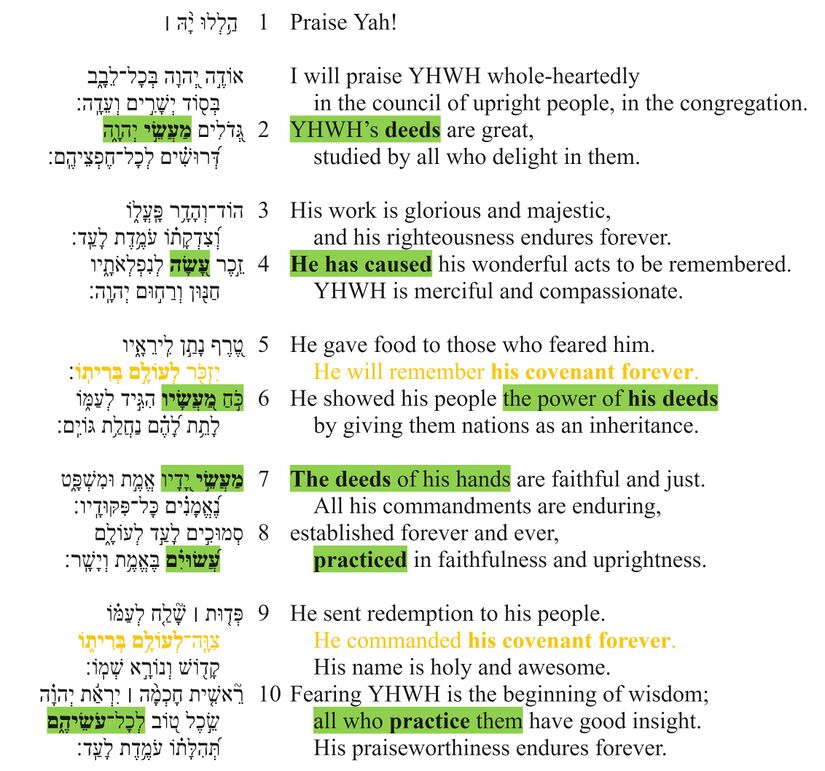

The root עשׂה occurs six times in Ps. 111 (vv. 2a, 4a, 6a, 7a, 8b, 10b), one time in each section and twice in the fourth section. The first four occurrences refer to YHWH's deeds (vv. 2a, 4a, 6a, 7a), and the last two occurrences refer to the deeds of YHWH's people (vv. 8b, 10b).

Another repetition in the psalm is phrase לְעוֹלָם בְּרִיתוֹ, which occurs in v. 5b and v. 9b.

Effect

The topic of Psalm 111 is YHWH's deeds (cf. vv. 1–2), so it is no surprise that the word "deeds" should occur so many times. The repetition thus functions to highlight the theme of the psalm. But the repetition also functions to make a point about how people ought to respond to YHWH's deeds. By using the word עשׂה twice with people as the agent, the psalm makes the point that the proper response to YHWH's deeds of faithfulness consists of deeds of faithful obedience. In short, the covenant relationship between YHWH and his people is to be characterized by doing (עשׂה). YHWH does great deeds for his people (vv. 2a, 4a, 6a, 7a), and, in response, his people do his commands (vv. 8b, 10b).

The two-way nature of this covenant relationship is emphasized also by the repetition of the phrase לְעוֹלָם בְּרִיתוֹ. The first time the phrase occurs (v. 5b) the focus is on YHWH keeping his side of the covenant. The second time the phrase occurs (v. 9b), the focus is on the people's obligation to keep their side of the covenant.

Repeated Roots

The repeated roots table is intended to identify the roots which are repeated in the psalm.

| Repeated Roots legend | |

|---|---|

| Divine name | The divine name is indicated by bold purple text. |

| Roots bounding a section | Roots bounding a section, appearing in the first and last verse of a section, are indicated by bold red text. |

| Roots occurring primarily in the first section are indicated in a yellow box. | |

| Roots occurring primarily in the third section are indicated in a blue box. | |

| Roots connected across sections are indicated by a vertical gray line connecting the roots. | |

| Section boundaries are indicated by a horizontal black line across the chart. | |

Notes

- The most frequently occurring word/root in the psalm is עשה (x6).

- The noun מעשה occurs 3 times.

- The verb עשה occurs 3 times.

- The root הלל occurs at the beginning (v. 1) and end (v. 10c) of the psalm.

- The quantifier כל occurs four times in the psalm. Especially striking is the correspondence between לְכָל־חֶפְצֵיהֶֽם (v. 2) and לְכָל־עֹשֵׂיהֶם (v. 10).

- In two cases, repeated roots occur with identical form and in an identical sequence.

- עֹמֶדֶת לָעַד (vv. 3b. 10c)

- לְעוֹלָם בְּרִיתוֹ (vv. 5b, 9b)

- The phrase לְעַמּוֹ is also repeated with an identical form in both v. 6a and v. 9a.

- The unmistakable repetition of לְעוֹלָם בְּרִיתוֹ and לְעַמּוֹ are part of a larger chiasm that spans vv. 5-9.

- The chiasm begins and ends with the root ירא (vv. 5a, 9c).

- Near the center of the chiasm, the combination of עשה and אמת occurs in v. 7a and v. 8b.

- The chiasm in vv. 5-9 is flanked on either side by the mention of YHWH's name (vv. 4b, 10a).

- Within the chiasm, YHWH's name is not mentioned.

- Some repetitions have no obvious structural function apart from short-range cohesion. E.g.,

- זכר (vv. 4-5)

- נתן (vv. 5-6)

- ירא (vv. 9-10)

- Two of these (זכר and ירא) stitch the seam between the embedded chiasm and the rest of the psalm.

Bibliography

- Allen, Leslie. 1983. Psalms 101-150. WBC 21. Waco: Word Books.

- Auffret, Pierre. 1997. “Grandes sont les œuvres de YHWH: Etude structurelle du Psaume 111.” JNES 56 (3): 183–96.

- Baethgen, Friedrich. 1904. Die Psalmen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

- Brettler, Marc Zvi. 2009. “The Riddle of Psalm 111.” Pages 62–73 in Scriptural Exegesis. Edited by Deborah A. Green and Laura S. Lieber. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dahood, Mitchell J. 1970. Psalms III, 101-150. AB 17A. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Ehrlich, Arnold B. 1905. Die Psalmen; neu übersetzt und erklärt. Berlin: Poppelauer.

- Fokkelman, J.P. 2003. Major Poems of the Hebrew Bible: At the Interface of Prosody and Structural Analysis (Vol 3: The Remaining 65 Psalms). Studia Semitica Neerlandica. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Gesenius, W. Donner, H. Rüterswörden, U. Renz, J. Meyer, R., eds. 2013. Hebräisches und aramäisches Handwörterbuch über das Alte Testament. 18. Auflage Gesamtausgabe. Berlin: Springer.

- Gordon, Amnon. 1982. “The Development of the Participle in Biblical, Mishnaic, and Modern Hebrew.” Afroasiatic Linguistics 8 (3): 121–179.

- Hensley, Adam D. 2018. Covenant Relationships and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies, volume 666. New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark.

- Hossfeld, Frank-Lothar, and Erich Zenger. 2011. Psalms 3: A Commentary on Psalms 101-150. Hermeneia. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress.

- Hupfeld, Hermann. 1871. Die Psalmen. Vol. 4. Gotha: F.A. Perthes.

- Hurvitz, Avi. 2016. A Concise Lexicon of Late Biblical Hebrew: Linguistic Innovations in the Writings of the Second Temple Period. Leiden: Brill.

- Jastrow, Marcus. 1926. Dictionary of Targumim, Talmud and Midrashic Literature. New York: Verlag Choreb.

- Jenni, Ernst. 1992. Die hebräischen Präpositionen Band 1: Die Präposition Beth. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer.

- ________. 2000. Die Hebräischen Präpositionen Band 3: Die Präposition Lamed. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer.

- Kiel, Jonathan M. 2022. “A New Thematic Structure for Psalm 111.” Page 107–128 in Like Nails Firmly Fixed (Qoh 12:11): Essays on the Text and Language of the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures, Presented to Peter J. Gentry on the Occasion of His Retirement. Edited by Phillip S. Marshall, John D. Meade, and Jonathan M. Kiel. Leuven: Peeters.

- Kohler, Ludwig. 1954. Hebrew Man. New York: Abingdon Press.

- Lugt, Pieter van der. 2013. Cantos and Strophes in Biblical Hebrew Poetry III: Psalms 90–150 and Psalm 1. Vol. 3. Oudtestamentische Studiën 63. Leiden: Brill.

- Niccacci, Alviero. 2006. “The Biblical Hebrew Verbal System in Poetry.” Page 247–68 in Biblical Hebrew in Its Northwest Semitic Setting: Typological and Historical Perspectives. Edited by Steven E. Fassberg and Avi Hurvitz. Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Press.

- Notarius, Tania. 2010. “The Active Predicative Participle in Archaic and Classical Biblical Poetry.” ANES 47: 241–69.

- Radak. Radak on Psalms.

- Robertson, O. Palmer. 2015. “The Strategic Placement of the ‘Hallelu-Yah’ Psalms within the Psalter.” JETS 58 (2): 165–68.

- Scoralick, Ruth. 1997. “Psalm 111 : Bauplan und Gedankengang.” Biblica 78 (2): 190–205.

- Weber, Beat. 2003. “Zu Kolometrie Und Strophischer Struktur von Psalm 111.” Biblische Notizen 118: 62–67.