The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind's Hidden Complexities

Introduction

Gilles/Mark Fauconnier/Turner, The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind's Hidden Complexities (New York: Basic Books, 2002).

At the 2025 International Cognitive Linguistics Conference in Buenos Aires, there was a session titled "Advances in Conceptual Blending Theory: Past and Future." The introduction to the session helpfully summarizes the history of Conceptual Blending Theory (CBT) and situates The Way We Think within that history:

- Thirty years ago, Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner published a technical paper (Report 9401) with the Department of Cognitive Science, University of California, San Diego, entitled 'Conceptual Projection and Middle Spaces' (Fauconnier & Turner 1994), aiming to describe 'a fundamental and general cognitive process, running over many (conceivably all) cognitive phenomena, including categorization, the making of hypotheses, inference, the origin and combining of grammatical constructions, analogy, metaphor, and narrative.' This theory went on to be developed most famously in their landmark book The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind's Hidden Complexities (Fauconnier & Turner 2002; see also Turner 2014).

- As predicted, Conceptual Blending Theory (CBT) has gone on to impact numerous fields across the cognitive sciences and beyond over the past three decades, with applications as broad as rhetoric and ideology (Coulson 2006), creative solutions from mathematics to music (Eppe et. al 2018; Gómez Ramírez 2020), cognitive poetics (Hiraga 1999; Sweetser 2006, Freeman 2008, 2020), painting (Morley 2016), courtroom discourse (Pascual 2002), advertising (Joy et al. 2009), memes (Coulson 2022), possibility studies (Hanchett Hanson 2023), sound design (Melvin & Bridges 2024), neuroscience (Pagán Cánovas & Valenzuela 2014), and science education (Fredriksson & Pelger 2018) to name only a handful.

An extensive and up-to-date bibliography is available on Mark Turner's website: https://markturner.org/blending.html.

Relevance to Psalms: Layer by Layer:

- We use Conceptual Blending Theory in our analysis of imagery.[1]

- We are exploring the use of Conceptual Blending Theory to analyze parallelism.

Summary

Key quotes from the Preface that summarize the topic and goal of the book:

- "In this book, we focus on conceptual blending... We investigate the principles of conceptual blending, its fascinating dynamics, and its crucial role in how we think and live" (v)... "Above all, it is our goal... to explain the principles and mechanisms of conceptual blending" (vi).

- "In this book, we argue that conceptual blending... is responsible for the origins of language, art, religion, science, and other singular human feats, and that it is as indispensable for basic everyday thought as it is for artistic and scientific abilities" (vi).

- "Conceptual blending operates largely behind the scenes. We are not consciously aware of its hidden complexities... Almost invisibly to consciousness, conceptual blending choreographs vast networks of conceptual meaning, yielding cognitive products that, at the conscious level, appear simple. The way we think is not the way we think we think. Everyday thought seems straightforward, but even our simplest thinking is astonishingly complex" (v).

Outline

- Part 1: The Network Model

- The Age of Form and the Age of Imagination

- The Tip of the Iceberg

- The Elements of Blending

- On the Way to Deeper Matters

- Cause and Effect

- Vital Relations and Their Compressions

- Compressions and Clashes

- Continuity Behind Diversity

- Part 2: How Conceptual Blending Makes Human Beings What They Are, For Better and For Worse

- The Origin of Language

- Things

- The Construction of the Unreal

- Identity and Character

- Category Metamorphosis

- Multiple Blends

- Multiple-Scope Creativity

- Constitutive and Governing Principles

- Form and Meaning

- The Way We Live

Part 1 explains Conceptual Blending Theory. Part 2 then argues that Conceptual Blending is pervasive and indispensable for everyday thought. This book summary will focus on Part 1 of the book.

Key Concept: Conceptual Blending

Illustration of Conceptual Blending: The Buddhist Monk

"A Buddhist Monk begins at dawn one day walking up a mountain, reaches the top at sunset, meditates at the top for several days until one dawn when he begins to walk back to the foot of the mountain, which he reaches at sunset. Make no assumptions about his starting or stopping or about his pace during the trips. Riddle: Is there a place on the path that the monk occupies at the same hour of the day on the two separate journeys?"[2]

Click "Expand" for the solution.

"Rather than envisioning the Buddhist Monk strolling up one day and strolling down several days later, imagine that he is taking both walks on the same day. There must be a place where he meets himself, and that place is the one we are looking for. Its existence solves the riddle" (39).

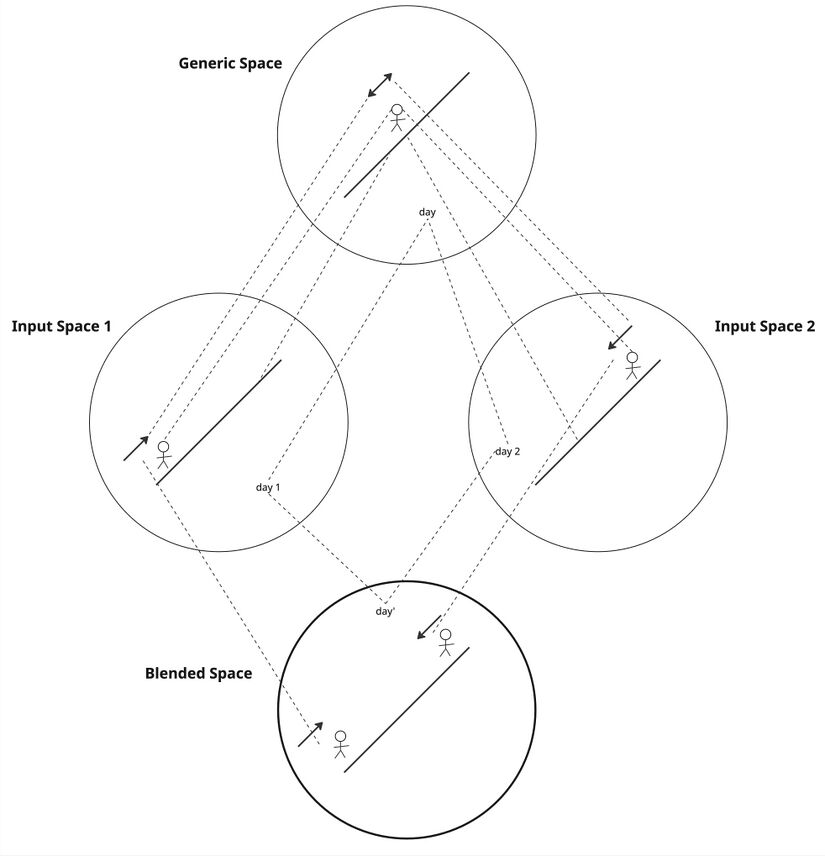

The mental operation involved in this imaginative exercise is an example of conceptual blending. It can be visualized as follows:

The Elements of Conceptual Blending

Mental Spaces

"Mental spaces are small conceptual packets constructed as we think and talk, for purposes of local understanding and action... They are interconnected, and can be modified as thought and discourse unfold... Mental spaces contain elements and are typically structured by frames" (40, italics added).[3] "So, for example, a mental space in which Julie purchases coffee at Peet's coffee shop has individual elements that are framed by commercial transaction, as well as by the subframe... of buying coffee at Peet's (102).

A blending network consists of at least four mental spaces: two input spaces, a generic space, and a blended space.[4]

- Input Spaces. "In the Buddhist Monk network, there are two input mental spaces... each... corresponding to one of the two journeys" (41).

- Generic Space. "A generic mental space maps onto each of the inputs and contains what the inputs have in common: a moving individual and his position, a path linking foot and summit of the mountain, a day of travel, and motion in an unspecified direction" (41).

- Blend. There is a fourth mental space, the blended space... Each of the mountain slopes in the two input mental spaces is projected to the same single mountain slope in the blended space. The two days of travel... are mapped onto a single day... and are thus fused. But the moving individuals and their positions are mapped according to the time of day, with direction of motion preserved, and therefore cannot be fused... The blend develops emergent structure that is not in the inputs" (41–42).

The blend develops emergent structure through a three-step process: (1) composition, (2) completion, (3) elaboration.

Composition

"Blending can compose elements from the input spaces to provide relations that do not exist in the separate inputs. In the Buddhist Monk example, composition yields two travelers making two journeys at the same time on the same path, even though each input has only one traveler making one journey. Counterpart elements can be composed by being included separately in the blend, as when the monks from the inputs are brought into the blend separately, yielding two monks; or by being projected onto the same element in the blend, as when the two days in the two inputs are projected onto the same day in the blend" (48).

Completion

"We rarely realize the extent of background knowledge and structure that we bring into a blend unconsciously. Blends recruit great ranges of such background meaning... In the Buddhist Monk case, the composition of two monks on the path is completed... by the scenario of two people journeying toward each other" (48).

Elaboration

"We elaborate blends by treating them as simulations and running them imaginatively... We run the Buddhist Monk blend to get the 'encounter' in the blend that provides the solution to the riddle" (48).

Compression

Blending also involves compression—the process by which conceptual blending reduces, or compresses, vast, diffuse relations between elements in the input spaces. For example, "When we see a Persian rug in a store and imagine how it would look in our house, we are compressing over two different physical spaces. We leave out conceptually all of the actual physical space that separates the real rug from our real house. When we imagine what answer we would give to a criticism directed at us years ago, we are compressing over times" (113). The Buddhist monk blend also involves a time compression: "two different journeys occurring at different times in history are brought together in a blend, thus in effect suppressing the time interval that separates them in history" (114).

More Examples of Conceptual Blending

- The Debate with Kant (59–62). "[A philosophy professor says to his class:] I claim that reason is a self-developing capacity. Kant disagrees with me on this point. He says it's innate, but I answer that that's begging the question, to which he counters, in Critique of Pure Reason, that only innate ideas have power. But I say to that, What about neuronal group selection? And he gives no answer" (59–60).

- The Iron Lady and the Rust Belt (18–21). "But Margaret Thatcher would never get elected here [in the US] because the labor unions can't stand her" (18).

- The Pronghorn (115–119). "The pronghorn runs as fast as it does because it is being chased by ghosts—the ghosts of predators past... As researchers begin to look, such ghosts appear to be ever more in evidence, with studies of other species showing that even when predators have been gone for hundreds of thousands of years, their prey may not have forgotten them" (115, citing a New York Times article).

- The Genie in the Computer (22–24).

References

- ↑ See Creator Guidelines for Figurative Language Analysis Background Knowledge, §14.

- ↑ From Arthur Koestler, The Act of Creation, cited on p. 39.

- ↑ The idea of a "frame" is similar to the idea of a "contextual domain" (cf. SDBH) or the idea of a "cultural script."

- ↑ "This is a minimal network. Conceptual integration networks can have several input spaces and even multiple blended spaces" (47).