Scripture as Communication

Introduction

Brown, Jeannine K. Scripture as Communication: Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007.

Jeannine Brown (PhD, Luther Seminary) is a New Testament scholar and professor at Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota. This is the first edition of the book. It has since been published with the same publisher (Baker Academic) as a second edition in 2021. The author notes in the preface to the second edition that it interacts with subsequent contributions on the topic of biblical hermeneutics, including non-Western perspectives. The second edition also includes more biblical examples and a glossary.

Summary

"Communication is inherently interpersonal" (p. 15).

Scripture as Communication: Introducing Biblical Hermeneutics explains, unpacks, and demonstrates the truth of this claim, and how it affects the way we interpret the Bible. The book is an accessible treatment of biblical hermeneutics that both introduces readers to the field and presents a case for a particular hermeneutic. Its primary focus, as the title suggests, is the nature of biblical texts––and indeed all language in use––as fundamentally communicative and interpersonal. The book summarises and draws on a variety of hermeneutical movements and approaches (e.g. Hirsch, Vanhoozer), and presents itself as theoretically "eclectic" (p. 46). In addition to its case for theory, the second half of the book addresses several practical concerns like the role of genre and social setting play in interpretation as well as how to "conceptualize contextualization."

Outline

For the full table of contents, click "Expand" to the right

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part 1 (Theory)

- Terminology and Context for Hermeneutics

- A Communication Model of Hermeneutics

- Authors, Texts, Readers: Historical Movements and Reactions

- Some Affirmations about Meaning from a Communication Model

- Developing Textual; Meaning: Implications, Effects, and Other Ways of Going “Beyond”

- An Invitation to Active Engagement: The Reader and the Bible

Part 2 (Practice)

- Genre and Communication

- The Language of the Bible

- The Social World of the Bible

- Literary Context, Intertextuality, and Canon

- Conceptualizing Contextualization

- Contextualization: Understanding Scripture Incarnationally

Summary Outline

—Chapters 1–2: Propose a communication model for interpreting the Bible.

—Chapters 3–6: Elaborate the proposed communication model.

—Chapters 7ff: Apply the model to various facets of the interpretive enterprise, e.g. genre, social setting, issues related to contextualisation.

Key Concepts

Hermeneutics

The main topic of the book is hermeneutics. Although Brown does not argue at length for a particular understanding of hermeneutics, she does not take it for granted that her readers share her understanding of the word or its goals. In short, hermeneutics is the study of the act of interpretation. This study includes "how texts communicate, how meaning is derived from texts and/or their authors, and what it is that people do when they interpret a text” (p. 20). Brown's short definition for biblical hermeneutics in particular is this: “the analysis of what we do when we seek to understand the Bible, including its appropriation to the contemporary world” (p. 21). This second-order task (i.e. "thinking about thinking") is important because communication always involves interpretation. The further one is removed from the time, language, and culture of the text, the fewer shared assumptions exist and the more difficult the task of interpretation becomes.

Meaning

Brown gleans insights from several linguistic and literary theories to construct her own hermeneutic position, including speech act theory, relevance theory, the literary theory of Hirsch, and narrative theology. In the communication model of hermeneutics, meaning can be understood as "the complex pattern of what an author intends to communicate with his or her audience for purposes of engagement, which is inscribed in the text and conveyed through use of both shareable language parameters and background-contextual assumptions" (p. 48).

Several statements support this this definition (pp. 47–48):

- Meaning is communicative intention, not mental act (Hirsch). The focus of interpretation is therefore on the implied author.

- Meaning includes both the locution and the illocution of a text, i.e. both its content and its force (speech act theory).

- Meaning is both explicit and implicit. Implications are part of a text's communicative meaning (relevance theory).

- Meaning is a linguistic expression set within background-contextual assumptions (relevance theory).

- Perlocutionary intention is an extension of meaning (speech act analysis). Although not the communicative act itself, the author's intended response is intimately linked to and can be derived from it.

Implied Author

The implied author is a hermeneutical construct intended to assist interpretation. It refers to the author presupposed by the text, and known through the text. The benefit of attending to the implied author instead of the empirical (historical) author is, according to Brown, that it allows us to move past introductory issues of authorship, date, etc., and focus on the communicative aims of the text. Note: The implied author need not supplant the historical author as a communicative agent (see Vanhoozer, Meaning, 239).

Key Arguments

Interpretive Model

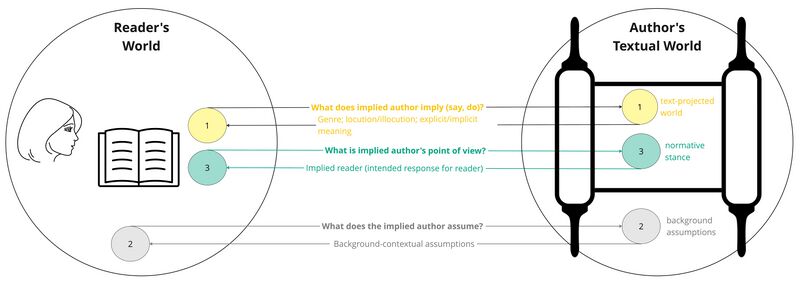

The communicative hermeneutic model can be imaged as a back-and-forth conversation with three movements. These movements are not sequential or singular, but each movement is concerned with an important part of meaning:

- textually projected world

- background-contextual assumptions

- normative stance

The first movement is the reader's engagement with the textual projected world. This requires attention to both locution and illocution, explicit and implicit meaning, and genre. The second movement requires the reader's attention to background-historical assumptions, which will include things like historical setting. And the third movement identifies the implied author's point of view, especially when there are multiple perspectives represented in a text. The image below is based on a diagram on p. 50:

Key Evidence

- Influential Secondary Literature

The book interacts with a considerable body of secondary literature, including the ideas of philosophers, biblical scholars, and theologians, primarily but not exclusively evangelical Christian. Most chapters conclude with "Suggestions for Further Reading," and the book itself has a helpful bibliography. Those whom Brown cites frequently include the following:

- Austin, J. L. How to Do Things with Words. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.

- Hirsch, E. D. Validity in Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967.

- Vanhoozer, Kevin J. Is There a Meaning in This Text? The Bible, the Reader, and the Morality of Literary Knowledge. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1998.

- Wright, N. T. The New Testament and the People of God. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992.

Impact

Important ideas

Affirmations about Meaning

Based on the understanding of meaning as defined in the book, a number of affirmations can be made (see ch. 4):

- Meaning is author-derived but textually communicated. Meaning can be helpfully understood as communicative intention. This affirmation values both the author and the text as axes of meaning, without veering into either extreme of "getting into the author's head," on the one hand, or the non-existent author, on the other.

- Meaning is complex and determinate. This affirmation resists the assumption that determinate meaning = singular meaning. To the contrary, meaning is complex (involving cognitive, emotive, volitional, and persuasive purposes), yet determinate (in Hirsch's words "a text's meaning is what it is and not a hundred other things") (p. 83).

- Meaning is imperfectly accessed by readers, both individual readers and readers in community. Interpretation is necessarily subjective, and our way of knowing truth is mediated. However, this does not mean that objective truth does not exist and is not worth pursing in the act of communication.

- Ambiguity can and often does attend meaning. The source of ambiguity differs, including lack of clear communication on the part of the author (excepting intentional ambiguity) and potential distance of time, space, language, and culture between the author and readers.

- Contextualisation involves readers attending to the original biblical context and to their contemporary contexts, so that meaning can be appropriated in ways that acknowledge Scripture as both culturally located and powerfully relevant. The central concern here is to understand the normative stance of the text, and to hear it within one's own cultural and personal contexts.

- The entire communicative event cannot be completed with a reader or hearer. Meaning proper can be identified with the author's communicative intent as inscribed in the text, but completion of the "actualised communicative event" cannot happen until the hearer responds. In speech act terms, meaning proper is captured in the locution and illocution, but communication is not complete until the perlocution is accomplished.

- The relational dimension of textual communication

- The importance of all three traditional domains of meaning: author, text, and reader

- The importance of perlocutionary intent as an extension of meaning (see p. 113)

Critique

Form and Meaning in Poetry

The main point of Chapter 7 ("Genre and Communication") is that genre is an important communicative choice of the author and therefore should not be ignored. However, while the main point is sound, the accompanying discussion of three major "genres" (poetry, epistle, and narrative) might be critiqued for its lack of nuance in the description of poetry in particular. The treatment of poetry assumes that poetic form (style) and semantics (meaning) are two separate entities, of which the latter decidedly takes priority in translation. This leads to questionable conclusions like this one about the word-play in Jesus' comparison of camel (gamlā) and gnat (qalmā):

"The same wordplay does not occur in English or Greek. Wordplays, as with all sound-based devices, seldom carry over into other languages without losing more meaning than is advisable in the translation (e.g. choosing 'mouse' and 'moose' to keep the wordplay in English would prioritize form over meaning to an extent that would make most translators shudder!) (p. 145, n. 23)."

While she is undoubtedly correct that sound plays rarely translate well, if at all, the assumption that the form of a text is distinct from its "meaning" is problematic, particularly for poetic texts.

Questions

An introductory book cannot address everything, so the following questions are less critique than follow-up questions:

- How should anthologies be handled? (i.e. when a "book" like the Psalter is the result of a long editorial process)

- How does positing more than one author affect this interpretive framework?

- How should readers understand the "implied audience" in the prayers of the Psalms? (see p. 76)

- Does our current exegetical process sufficiently allow for this back-and-forth, iterative process to happen the way it should?